Gary Kachadourian

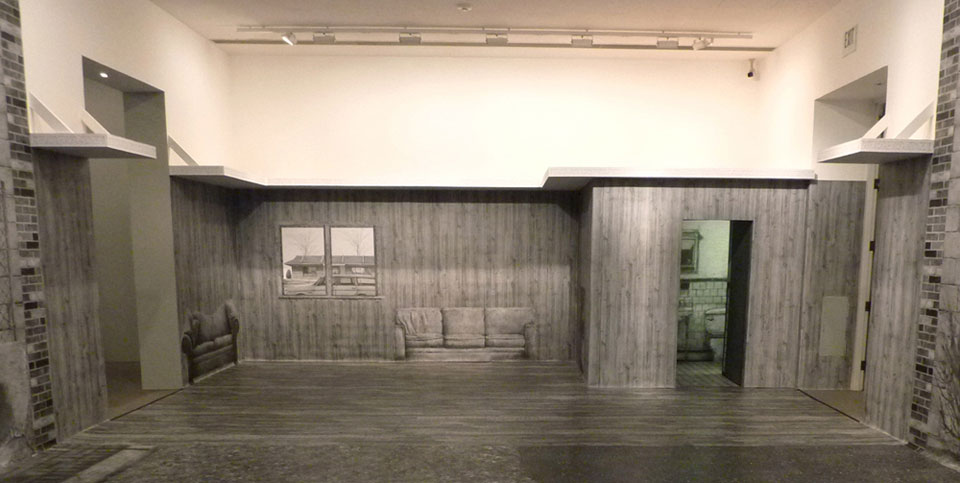

Gary Kachadourian, Large format xerographic prints and corrugated cardboard, 11′ x 20′ unfolded, 4″ x 12″ x 9″ in box, 2012

Laconic is a word that comes to mind when not only speaking with Gary Kachadourian but also when engaging his artwork. He is eminently likable and articulate but seemingly allergic to self-promotion, Gary could be a charter member of Understaters Anonymous. As an arts administrator, curator, and now active visual artist himself, he has been a constant and vital presence in Baltimore cultural life for most of his adult life.

His drawings are an index of the urban quotidian, dumpsters, utility boxes, weeds, empty lots, port-o-potties, jersey barriers, and parking booths, rendered precisely without a trace of subjectivity or editorial comment. His largely black and white installations are as funny and familiar as they are ambitious and labor intensive. To step inside one is an experience in quiet disorientation; suddenly the world of color and three-dimensionality somehow seems alien, as if we have been living in the wrong dimension all along.

This conversation took place in my backyard in Baltimore on June 3, 2014.

MAD: You must like to draw.

GK: Yes, drawing is fun. (Laughter). But I should qualify the word “fun”. It is still a serious endeavor it’s just that I’ve found that I produce better work and more work if it is also “fun” to do. It’s kind of a weird thing, drawing for me fits into the tradition of retiree’s pastimes like whittling and knitting. It’s a repetitive and soothing process that leads to something. Its like scratching yourself or watching television, you can do it all day. My artmaking is built on that process, if it’s “fun” to do I don’t have to overcome my bad work ethic issues. Also, I always had a job at the same time I was making art, so if it’s “fun” to do I am more likely to do it. In a sense, you try to pick the thing that is closest to playing Tetris to fit your personality. That being said, some things are really hard to draw, so I have to balance the “fun” and the difficult.

MAD: One of the many interesting contradictions of your work is that it has no immediately obvious personality or style. The old romantic notion of ‘personal expression’ is beside the point. Do you think that is accurate?

GK: That is designed into my approach. I like the distancing of not having an apparent style. I’ve always preferred to have conversations with people not when we are facing each other but are turned in the same direction, so we don’t have to look at each other when talking. Eye contact is distracting. So I try to build in a process of removal. I started as a printmaker, that is also a process of removal in that you make an object and then you transfer it onto another object. The removal of personality is also a philosophical thing. I like it when you can’t really tell who made things; it makes it more mysterious.

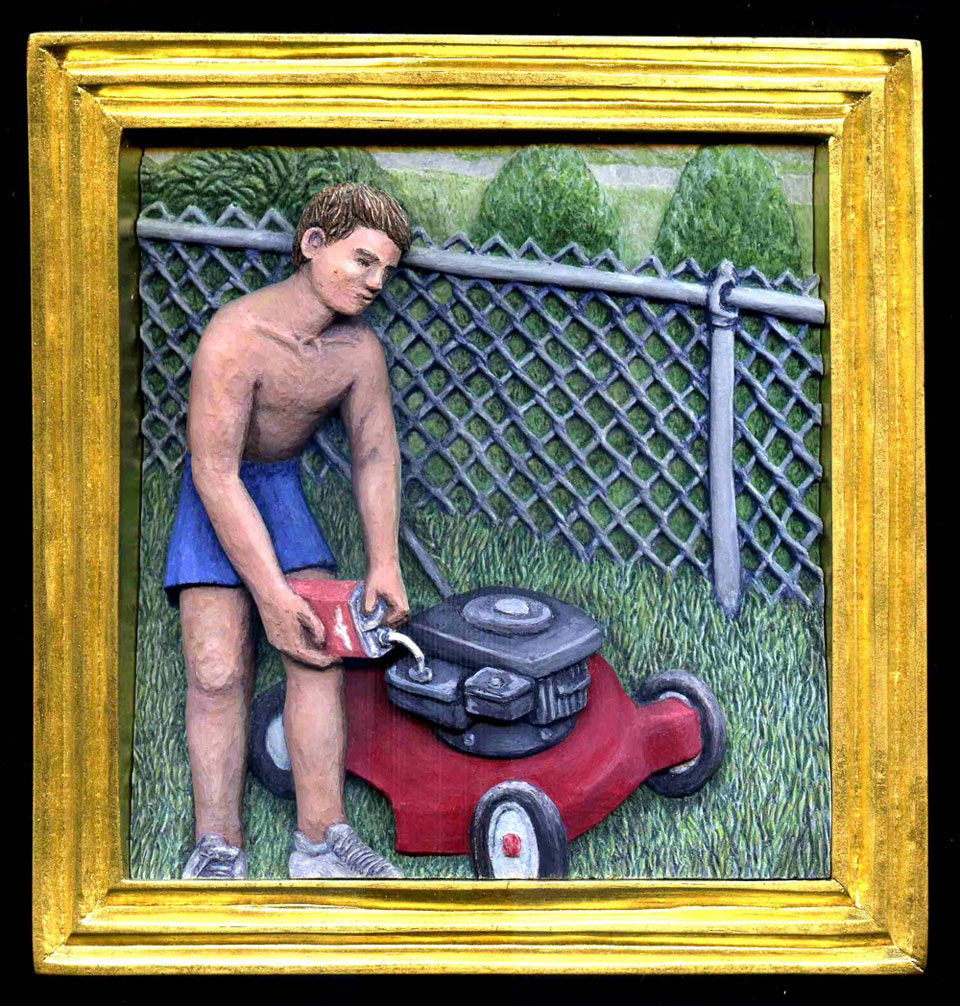

MAD: I recently learned of some earlier work of yours that are woodcarvings, you made starting in the 1990s.

GK: I made them for about 10 years.

MAD: I think they are amazing, sweet little hand carved objects of banal moments like someone watering the lawn, a dandelion popping up in the grass, a bicyclist taking a rest, someone entering a tent. They are like hand-made snapshots. There is a kind of nostalgia in both the subject matter and the process and materiality – hand-painted, hand-carved wood? Talk about craft and authenticity!

GK: Carving is like drawing, its easy for me and, once again, fun. Earlier I mentioned that people used to pass the time by knitting and whittling and carving is in that tradition, it’s a comfortable place for me. Arriving at it as an artmaking process was also conceptual. Because the object looks like it was made slowly and carefully, your subject matter gets an added weight. So you can do a guy putting gasoline in a lawnmower and because it’s carved out of wood it seems important somehow. It was also a way of getting around a weakness I had when I tried to paint. I could never merge the color and the drawing as one process. Because the carving does most of the work in providing texture, shading and perspective, it functioned as a support for the color.

Also I was making that work when I had young kids and it could take months to carve one of those figures. When raising kids you learn there is a special layer of wasting time, or lost time, so I could carve while still keeping an eye on the kids while they played. Much of my work is based on the idea of ‘art you can make while sitting on the sofa.’ Standing up in the studio it is much harder to make art after working all day and then putting the kids to bed.

MAD: The subject matter is very photographic, like snapshots of in between moments, the banality of the everyday. But they are the opposite of snapshots in that they represent an enormous investment of time, it must have taken weeks to carve them.

GK: Again, the banal is a big part of raising kids. (Laughter) Also, regarding them being like snapshots, interestingly, I hardly ever used photographs for the carvings. They were almost always done from memory with some field sketches for details and only the occasional photograph/snapshot for color.

MAD: Was this the birth of your interest in banality?

GK: It has always kind of been there but the carvings were the first time I think I got it to work for me. But after doing the carvings for a while I started to realize that I was not good at nor was I really that interested in the figure. Up to that point I always thought the figure was necessary in representational art.

Gary Kachadourian, Life-Size Pepsi Machine Printed Sculpture on Site of Original Pepsi Machine, 84″ x 42″ x 40″, Baltimore 2012. Photo by Martha Cooper

MAD: But what they do have in common with your more recent work is this duality or internal contradiction or tension between the monumental and the banal.

GK: Yes, I agree. There is a commonality in some of the ideas but they are manifested in opposite ways, from the carefully crafted one of a kind diminutive object to a carefully crafted drawing that is reproduced in multiples.

MAD: Another duality or internal contradiction in the work is that it is immediately accessible, in that most people could identify what the image is, there is an ease of acknowledgement, ‘oh, that’s a drawing of a phone booth, or a dumpster’, the work resists interpretation and therein lies it’s laconic power. It’s mundane and inscrutable simultaneously. Do you think that’s a fair assessment?

GK: Yes, I like that the work does not have a direct meaning. I am making stuff you can just look at. You can buy a poster or a drawing of a utility box from me and except that it is in black and white and on paper that folds up, it is not any different from the one you drive by everyday on the street. I try to design it so that it could mean a lot of different things to different people. Or maybe it means nothing. It could be just like the thing you always ignored, like a cinder block wall or because it is art now, it might lead you to think about it in different ways. Either way is OK with me.

MAD: As you were speaking I was trying to examine my assumptions about art’s purpose in the broadest sense. One assumption is that art is meant to refresh perception so that we re-appreciate the world in some way, although I am not sure that’s what it is for me. I think art can heighten perception but more so about the specific image or object under consideration. It does not necessarily ennoble all future encounters with similar objects in the world. I don’t look at your Jersey Barriers and imagine it will inspire me to reassess my thinking about concrete roadside barriers on the highway. I like the thing that you made!

GK: It is a process of removal. One of the other things I did with the kids was to build model trains, and I became obsessed with watching trains go by, looking a railroad tracks, and all the junky things you see by the sides of the tracks. I began to appreciate stuff that I thought was stupid and ugly before. Now I kind of admire dropped ceilings and jersey barriers. So whether or not you get to re-appreciate it doesn’t really matter to me, I feel like there is a reason for the piece to exist, although I am not sure what it is.

MAD: In your work there are connections to a whole host of conceptual and process artists from the 1970s, Gordon Matta-Clark and Sol Lewitt, most obviously come to mind. But more unusually and perhaps more importantly is the hobbyist: the guy fiddling around in his garage or basement making stuff.

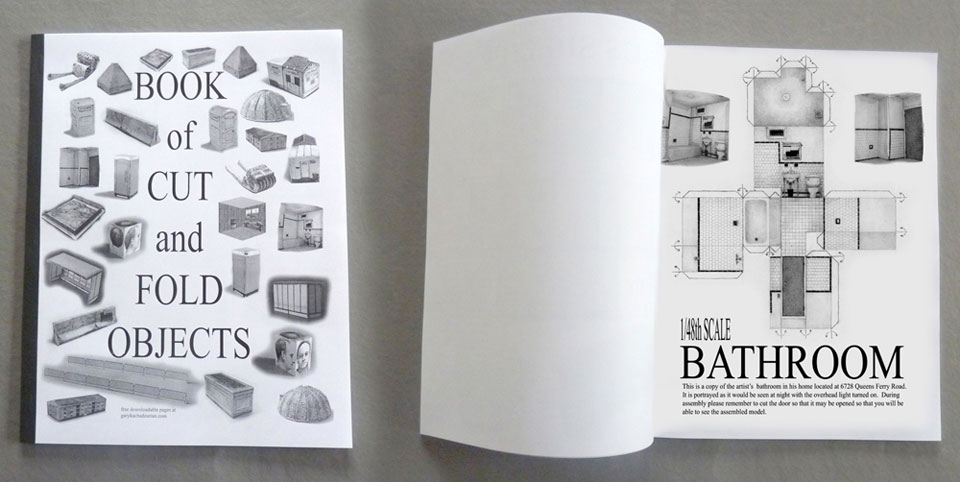

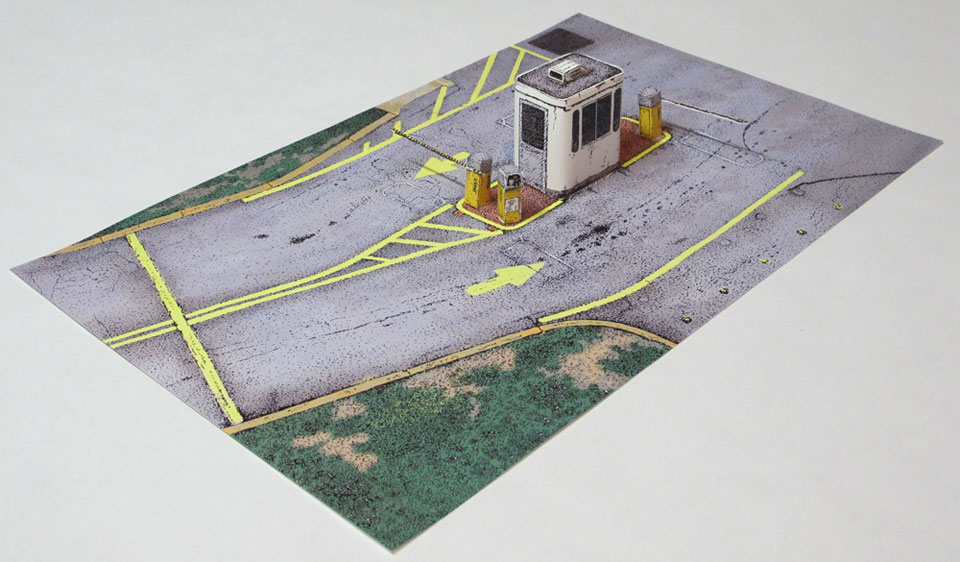

GK: The hobbyist is the center or probably more accurately the source of everything for me. The hobby catalog and toy catalog, like the matchbox toy car catalog, are major influences, formally and in terms of content. I was obsessed with these things as a kid. Yes the conceptual art stuff is there, especially Ed Ruscha’s books, but when you get down to it, for me, the same pleasure is derived from looking at Ruscha’s ’26 Gasoline Stations’ and looking at the Auto World model car catalog. I don’t mean to say that a catalog is art or that Ruscha’s books are catalogs, just that they have similar formal characteristics and create similar feelings of pleasure when looking at them. Regarding the models in the catalogs, there is also the pleasure in building, getting these kits and spreading out all the parts and finding the ways they fit together.

MAD: That makes me think of the German photo conceptualist Hans Peter Feldmann who takes similar interest in vernacular photography, he makes vast photo albums of bikini-clad women, soccer stars, or desserts. He left the art world for almost 20 years and ran a novelty toy store, and he collected and sold decorative thimbles.

GK: I always wanted to curate a painting show based on this guy who paints model railroad cars to look like they are covered in rust. He buys the model railroad car that was already painted with the logo and then re-paint’s it to look like a beat up rusted one. They are pretty quickly done so he can sell them at a reasonable price so they aren’t exquisite models, you can see all of the brush strokes. This makes them not great static models but isn’t a problem if they are moving or part of a huge layout, but if you look at them individually as paintings, the brushwork is beautiful. There is an overlap between the two worlds. I think the art world suffers from not acknowledging its other sources, since it is so much about presentation of things for other people to appreciate.

MAD: I did a Saint Lucy conversation with Nayland Blake last year and we discussed some works he did in the early 90s I think, which were sculptures made with paperback books he got at second hand stores. He collected series or multiple copies of pulp novels, Stephen King and the like for these shelf pieces. He talked about how as young artists especially, when asked what one is reading, we usually answer with whatever trendy theoretical text is relevant at the moment, and we never admit to the pop stuff we are consuming, as if that is not an influence, as if some things are beneath consideration, that there might be something shameful, embarrassing or not serious about feeling influenced by ‘Lord of the Rings’. In our efforts to be taken seriously, we have to show off how smart we are instead of being honest about how we consume and internalize the esthetics of popular culture, whatever form that may take. I think that has changed a bit recently and younger artists are more embracing of this.

GK: There is so much overlap; the influence of advertising on art is an obvious example. In terms of audience the art world is a very narrow demographic, the artist has to address in some manner, the collector, the critic, the intellectual, but it’s a pretty small group. But by doing that you sometimes eliminate the potential for a larger audience.

MAD: You have varied drawing styles from carefully rendered precise observational things to messy, somewhat casual, looser drawings, I am thinking here of the hot rod cars and engines, which make me think of underground comics from the 1960s. They have a sort of wild-eyed, drug-induced quality.

GK: Obsessive doodling from a very early age will do that, so there is this echo of 60s ball point pen drug inspired drawings. But instead of independent comics it’s the stuff right before that, Ed Roth, hot rod cartoons and decals, MAD Magazine. MAD still resonates, I just watched The Valley of the Dolls recently for the first time. I first read the parody of that film in MAD Magazine when I was a kid and I realized my expectations for it were completely formed by MAD. Even more influentially, I went to a hot rod show when I was about 12 and watched an airbrush artist customize a T-shirt with a Barracuda popping a wheelie and that was the coolest thing. I learned a lot about drawing watching him do that painting. So those drawings you are talking about, the car and motor drawings, are things I perfected or at least thought I perfected in the 7th and 8th grade.

Gary Kachadourian, 1/48th Scale Parking Attendant Booth (built kit from Drive-Thru’s book), color laser prints, 2″ x 10″ x 16″ built, 2014

MAD: You went to art school and then had a very successful career as a curator and arts administrator. You left that career to become a full time practicing artist. That is the opposite trajectory of how many others have done it, where after a time of trying to make it as an artist they take an administrative job in the arts which then incrementally becomes their career.

GK: I don’t know why that path is unusual, it shouldn’t be but it is. So yes I went to art school and then got an arts administration job, which at the time, if one didn’t teach, one did that. It seemed like half the people I worked with were artists and the other half were art historians, which was a good mix since you had people who were good at writing grants and others who understood the process of making. But if you do that job for a while it’s hard to continue to make art, I think I was an anomaly in that sense. The curatorial aspect was really helpful for me to think about how art works and what it was, or was not, for me.

Gary Kachadourian, Forest / City, large format xerographic prints installed at Western Carolina University, 23′ x 37′ x 48′, 2014

MAD: I wanted to talk about your installations, which are essentially your drawings of the mundane and the quotidian, enlarged through photocopy to create large-scale immersive environments. One of the things I really love about them is that when I walk into your black and white world I am still in color. And although there is a monumental aspect to your installations, the imagery is largely two-dimensional. So as I move about and watch others in that space I experience a perceptual disorientation, a kind of displacement in which I understand where I am but I feel that I am not real somehow.

GK: That was not part of the plan but a product of the process. I had been making single objects life sized but it wasn’t until I made a black and white environment by making multiple walls and floor that connected that it occurred. It was a welcome surprise. I like the effect a lot but I don’t want to deliberately design for it to happen because it somehow feels like a trick even though I think it is really good, maybe it’s a bit shallow. Maybe because it was an accidental outcome I am afraid of becoming dependent on it.

MAD: Selling your miniatures and books at book fairs are a big part of what you do. You always have a table at the New York Art Book Fair for example. I’ve seen you selling drawings on the street with a little stand and display racks. I am not saying you are performing, but there is something performative about the way you occupy these spaces like a merchant.

GK: There is something performative about it but again I don’t want that aspect to be calculated. It is about the presentation of ideas within a specific community, but in the end I am the artist trying to sell my work. Being at the New York Art Book Fair is like participating in a big group show, it’s not necessarily the best venue to show your work but it’s really great to meet and talk to all the other artists and to all of the people that attend the event. I like sitting and talking so from that point of view it’s perfect for me, from a sales point of view, it’s okay but that is secondary. It’s great to play the salesman but there is a fear that I may start to become a salesman and start worrying about making sales and adjusting the art to that goal, even if unconsciously.