David Levi Strauss

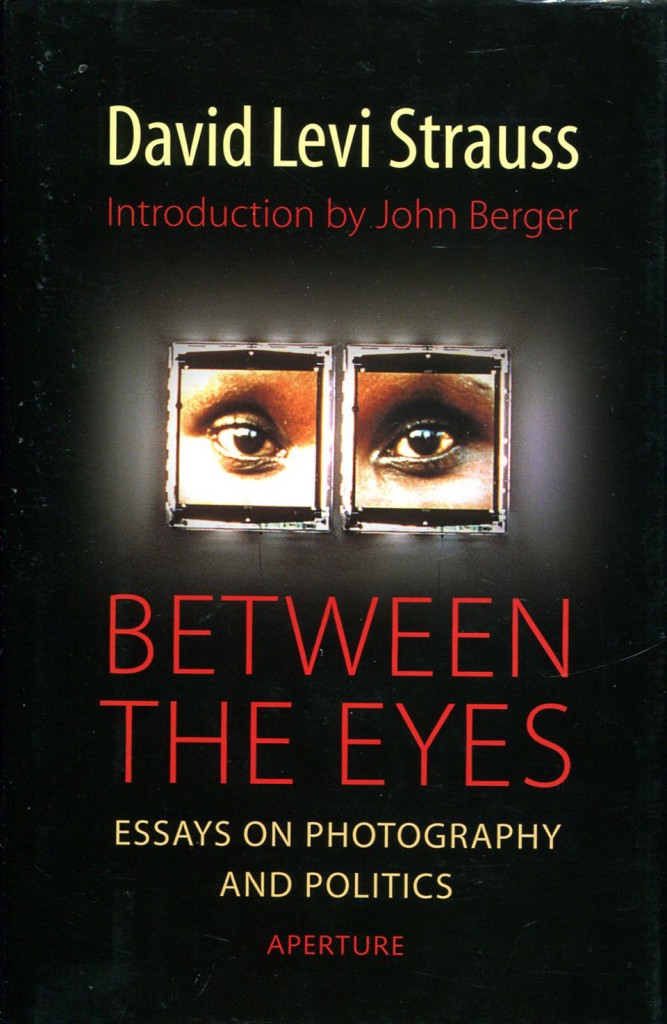

David Levi Strauss is a writer and critic in New York. He is the author of From Head to Hand: Art & the Manual (Oxford University Press, 2010), Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics, with an introduction by John Berger (Aperture 2003), and Between Dog & Wolf: Essays on Art and Politics (Autonomedia 1999). His new book, Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow: Essays on the Present and Future of Photography was recently published by Aperture. Strauss was a Guggenheim fellow in 2003-4 and received the Infinity Award for Writing from the International Center of Photography in 2007. He was on the faculty of the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College from 2000-2005, and is now Chair of the graduate program in Art Criticism & Writing at the School of Visual Arts in New York.

I first met David Levi Strauss (or Levi as he likes to be called) in San Francisco in the mid-1980s. I thought he was the most serious person I had ever met, nice, but serious. It took me a while to appreciate the subtle humor and intellectual generosity that suffuses his manner and speech. His commitment to writing incisively and accessibly about art, photography and politics is fueled by compassion, curiosity and an unquenchable desire for justice. I have admired him from close up and from afar for all these years.

This conversation took place in his office at the School of Visual Arts on May 22, 2014.

MAD: I know you have had a life-long interest in poetry, but I am curious about how you came to write critically about photography. You were a student at the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, right? Were you interested in being a photographer as well? And if so, was there a division within yourself, or did you find a way to do both?

DLS: Yes, always both. I was a poet first, but I started making photographs early on. I went around the world on a ship, a floating university, when I was 19, and I took a lot of photographs, all over the world. Then I went to Goddard College and studied photography and writing, so I was writing poetry and taking photographs all that time, and trying to put them together. Then I went to Visual Studies Workshop in 1975 and 76 and was trying to put the two together in the same space, on the same surface.

At VSW, I started writing for their journal, Afterimage, but when I first started writing criticism there was a tremendous schism between the poetry and the criticism, and it caused a conflict.

MAD: Did reading Sontag catalyze that?

DLS: That was part of it. As I say in my essay on Sontag in Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow, Sontag’s book On Photography had just come out when I got to VSW and the attitude toward that book among photographers was pretty hostile. I found myself on the other side; her book catalyzed what I thought writing about photography could be. It was Sontag, Roland Barthes, and John Berger who were the models, and Berger was by far the biggest influence. When I saw what he was doing, I knew something else was possible, but it was not an easy transition. It wasn’t so much a conflict between making photographs and writing about them, it was between poetry and criticism, so I stopped writing criticism. I picked it up again later in San Francisco and eventually that conflict disappeared; at a certain point, it was all just writing, and I realized I could do both.

MAD: When we first met in San Francisco in the mid-1980s, I think you were driving a cab at night and you wrote after your shift.

DLS: Yes, I drove a cab for nine years in San Francisco, always at night, and usually just on the weekends. This was the most dangerous shift, but also the most lucrative, if you could manage to hang on to your cash. I got to be good at it, and I could make a living working only two or three nights a week, and write the rest of the time. I loved driving at night, and became entirely nocturnal.

MAD: I ask because you are famously a night owl and you still write through the night. Did that start with the taxi driving?

DLS: Yes.

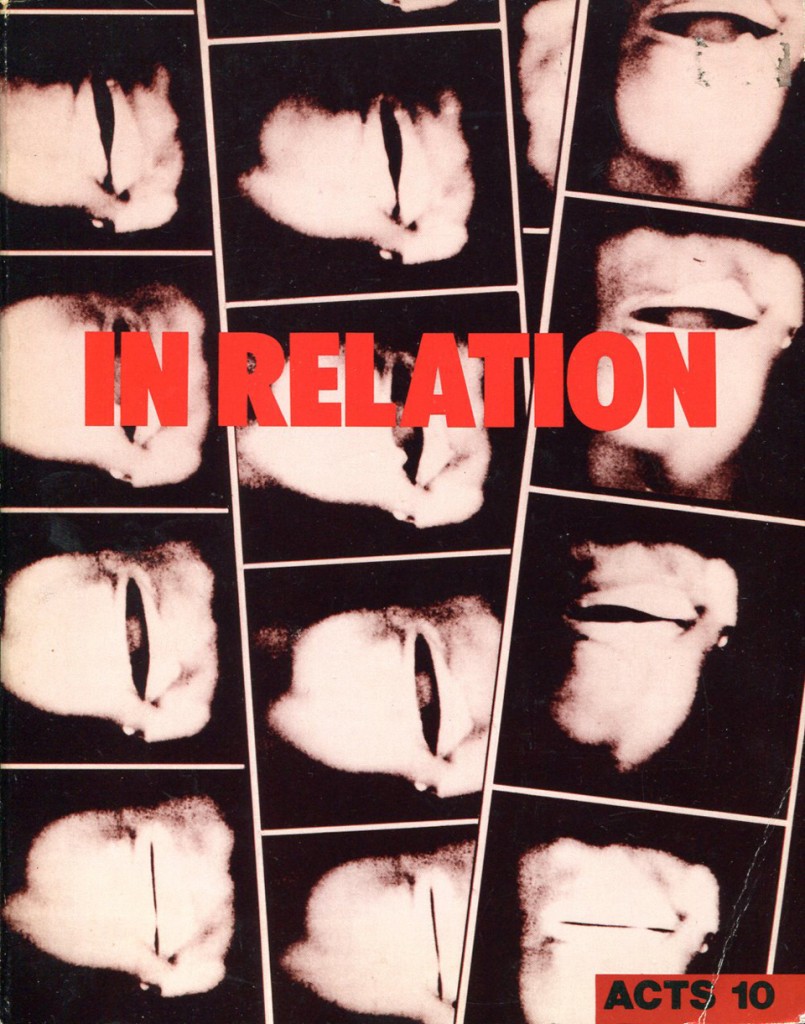

MAD: During this period you started and edited a literary journal called ACTS. What were your goals with that journal and how many issues did you publish?

DLS: I started printing the journal in the poet Robert Duncan’s basement, and it was originally intended to be the house organ of the Poetics Program that I was in from 1980 to 85. So the first issue included only the poets and writers who were teachers and students in the program—Robert Duncan, Diane Di Prima, David Meltzer, Michael Palmer, Duncan McNaughton, Leslie Scalapino, Anselm Hollo, Robert Grenier, Susan Thackrey, Sarah Menefee, Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Aaron Shurin—and it grew out from there. The first issue was mimeographed; Duncan had a mimeograph machine that he had printed his Dante Etudes on, and he bought the paper for me to print the first issue. Then I applied and got some National Endowment for the Arts grants and we eventually published 10 issues of the journal. When the NEA pulled our funding during the Culture Wars, ACTS died practically overnight. I’m sure that happened to a lot of literary journals during that period.

MAD: How did publishing ACTS influence how you thought of yourself as a writer and how you might proceed?

DLS: I loved doing it. I called it ACTS because I wanted to act on the world, to engage. My coeditor Benjamin Hollander and I did several book issues, including one on Jack Spicer called A Book of Correspondences for Jack Spicer, and one on Paul Celan’s work called Translating Tradition. I think it was the first thing on him in English, well before the academy turned the study of his work into an industry. ACTS put me in contact and dialogue with people in the poetry world in a way that wouldn’t have happened any other way.

MAD: I’m not sure what issue it was, maybe #10, that had the title In Relation, and it had a significant impact on me. It’s hard to pin down exactly why, but it had something to do with my (late) realization that meaning is made in relationship between things, that things don’t have intrinsic meaning, but that we establish meaning vis a vis. It made me examine how I interacted with images, texts and objects and even other people in terms of how I interpret through myriad and unexamined filters. I had never really thought about that before, I’m embarrassed to say. I am not even sure that was your goal, but there it is.

DLS: It was my intention, and a good deal of that was focused on the relation between word and image. Even now, when people talk about images they often talk about them as if they appear by themselves, but they are almost always accompanied by text, and it’s always a relation between the two where meaning is made. It’s a difficult thing to analyze because it is happening in two different parts of the brain, and it gets very complicated.

MAD: You were in San Francisco for 15 years, which has a rich literary tradition and you worked closely and were friends with many poets over the years. It must have been hard to leave. Did you come to New York because you had goals as a critic and you needed to be here?

DLS: Yes. It just became clear that I needed to publish books, and I couldn’t do it there. Everyone I was writing for, all the art magazines, were in New York or in Europe, and it just became less and less tenable to remain in San Francisco. I needed to be in New York for the writing to find an audience. And a big part of it, also, was that Robert Duncan died and this tremendous community that had sustained me started to break up. The hardest thing was to leave dear friends there.

MAD: Were you ever drawn to Los Angeles?

DLS: Not really. Growing up in Kansas, the romance was always with New York. I always thought that I would end up here. The romance continues to this day; every time I drive over the George Washington Bridge, I get excited and feel like anything could happen.

MAD: I have a few questions about your book Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics. In John Berger’s introduction, he talks about the “systematic abuse of language.” This has been a concern of many writers, George Orwell and Noam Chomsky just to name two obvious examples. This struggle against the abuse of language is a struggle that never ends. And it is quite evident in how carefully you choose your words. Not only to express your ideas and to make them accessible, but just as importantly, to oppose lies and obfuscation. Do you think that is an accurate statement?

DLS: Absolutely, and that is why Berger was such a big influence, because I saw that he was able to write about very complicated subjects in a direct and beautiful way, and that’s what I wanted to do. And I always saw that as having an implicit politics, writing that way for a general audience, with no jargon, and no specialized language. Through Berger, I understood that as a political choice.

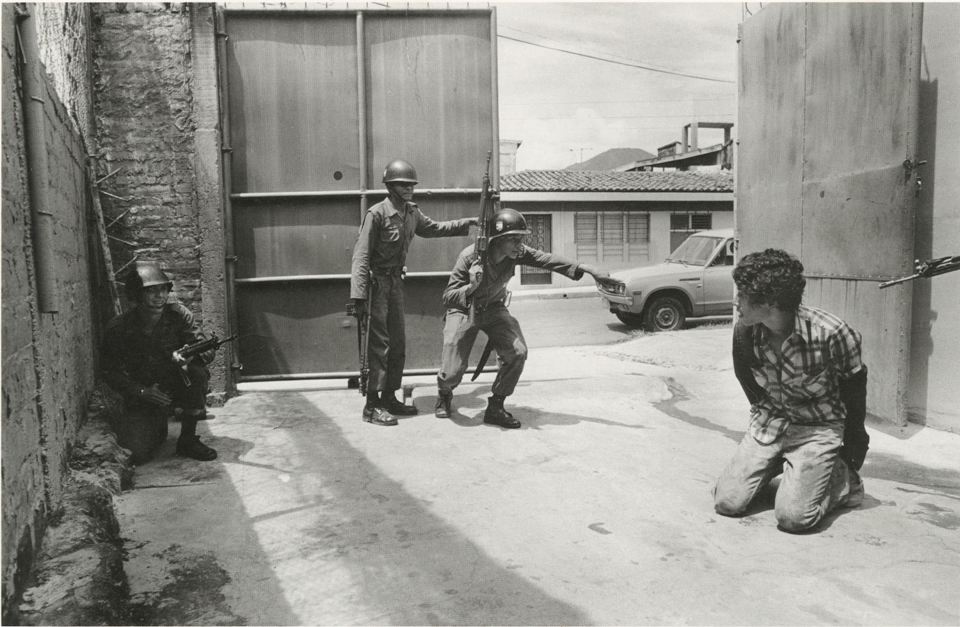

John Hoagland, arrest of auto repair mechanic for failure to carry an ID card, San Salvador, 1979-1983

MAD: In your essay “Photography and Propaganda,” you write about two photojournalists who worked and died in Central America in the 1980s, Richard Cross and John Hoagland. You discuss Hoagland’s emphatic insistence that he did not believe in objectivity, yet he also just as emphatically refused to be a propagandist for anyone or anything. In this sense, he questions the conventional suspicion of subjectivity. As if the refusal to recognize or believe in the false ideal of objectivity negated the value of subjectivity itself.

Hoagland and Cross were dissidents in the machine of the news media, and you take specific news organizations to task for manufacturing untruths under the guise of objectivity. I know this essay won the Logan award for new critical writing on photography, yet the granting organization, the Photographic Resource Center in Boston, refused to publish it as it had every other previous winner. Can you talk about that?

DLS: Sure. What I heard was that although the jurors, Nathan Lyons and Anne Wilkes Tucker, liked it and chose it, others involved in the grant did not like the politics of the essay, and didn’t want to publish it. It was finally published in its entirety in Afterimage, thanks to the courage of David Trend, who was then the editor.

MAD: Because it pointed fingers and was deemed accusatory of powerful news organizations? It may be provocative but it is a well-reasoned argument.

DLS: I was shocked by the response. Mind you, I did not find out from them, this is what I heard later from people who knew something about the process. It had a big effect on me at the time. It had all started when I saw a show of Hoagland’s and Cross’s work at Eye Gallery in San Francisco. I met Susan Meiselas around this time as well. In the early 90s, there was a very strong critique of documentary practice being made. You couldn’t talk about documentary work without coming up against this argument about the aestheticization of suffering. And I knew that this critique fundamentally misrepresented what Hoagland and Cross, or Meiselas, were doing.

I think that the aestheticization of suffering critique was a substantive critique, and it needed to be done, but it went too far and discounted the political role of the subjectivity of the documentarian. That to me was a glaring omission, and I spent a lot of time trying to deal with that in the writing. I revisit it in my current book, in an essay called “Troublesomely Bound Up with Reality.”

MAD: This issue continues to this day. I had the opportunity to interview Tim Hetherington about a year before he was killed in Libya, and he continually faced the ethical questions of what it meant to document war and tragedy. He sometimes literally put the camera down for long periods of time in order to physically help as he did in Liberia after the civil war. But he fundamentally believed in the mission of the witness, that to not witness is an even greater sin. He was always trying to find new forms and new contexts for the work in the attempt to reach broader audiences.

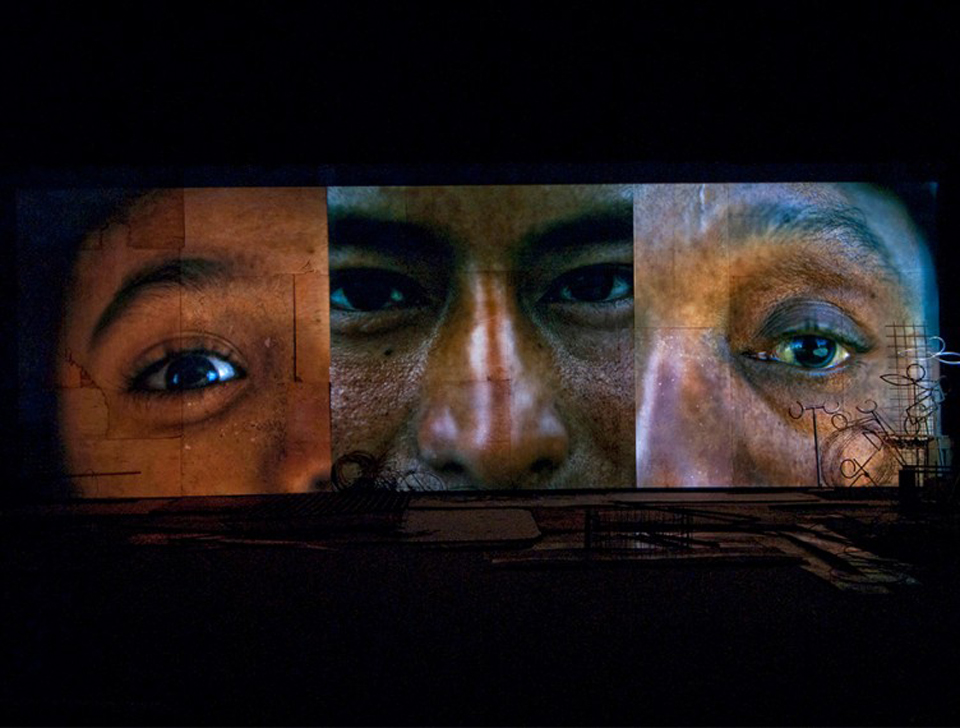

DLS: There are many examples of contemporary photojournalists coming to grips with this. I spoke with Jim Nachtwey about the issue of trying to control the work and the way it is presented once it leaves you, when all these errant meanings come in. And Susan Meiselas has tried every way you can think of to place the work in a context in which the work opens up rather than closing down around fixed news tropes.

MAD: The last essay in Between the Eyes is a lovely and lyrical piece of writing inspired by Miguel Rio Branco’s installation “Between the Eyes, the Desert.” Instead of being an expository treatment of the work, it is more an exploration of the internal life of images, or our internal life with images. Excuse how simplistic this might seem, but after reading it I was thinking about how in writing there are these twin poles of the expository and the lyrical. In photography we have similar twin poles, the documentary and the art photograph. This is a long-lived dichotomy—a hundred years ago Lewis Hine and Alfred Steiglitz embodied these seemingly divergent approaches: social work versus camera work. Obviously these things are not mutually exclusive, but maybe it’s a useful distinction.

So it’s interesting to me that this collection of essays ends in a place where your own deep and lifelong inclinations toward the poetic and the critical are synthesized.

DLS: I first saw Miguel’s work uptown at Throckmorton gallery, and it knocked me down. I wrote something for Artforum about it and then he contacted me and that started a collaboration that went on for a number of years. He asked me to write an essay for his Aperture monograph, which is where the “Beauty and the Beast, Right Between the Eyes” essay first appeared. In the essay at the end of Between the Eyes, I imagine what the people in Plato’s Cave were thinking about. In both of these essays, I was pleased to be able to write more lyrically in relation to images. It opened everything up for me, and it all seemed possible, that I could write what I needed to write. I was a poet first and then I became an essayist, primarily because there were so few limits on what you could do in that form, at that time.

What you say about the split between documentary and art photography is true, and that split always seemed strange and arbitrary and worth contesting, to me, because the two are often mixed. And probably the work that has the most influence, the most affect, is work in which those fixed categories are threatened.

MAD: Someone like Robert Frank, for example.

DLS: Exactly. His work was a real threat. People forget that when The Americans first appeared, the art photography community was outraged, largely because that work threatened the categories.

MAD: I say this to my students, and to myself, all the time: “Pay attention to your resistance,” because when you resist something, a boundary is being tested, and your boundaries should be examined. Are they ethical boundaries, esthetic, political? Do they come from the culture, from your parents? Boundaries are important but they should be yours and should be useful and not limiting. I think you are right that when The Americans came out, it called into question the meaning of documentary. Your ongoing concern for things “in relation” reminds me of what James Baldwin said: “If I am not what you think I am, then you are not what you think you are either.” When someone challenges or redefines a category, then everything else must be redefined in relation.

DLS: Absolutely. For our generation, Robert Frank did that. Then you get to Larry Clark and Tulsa, which blew another big hole in the idea of documentary. What is the documentarian’s relationship to the subject? What happens when he or she is inside the story?

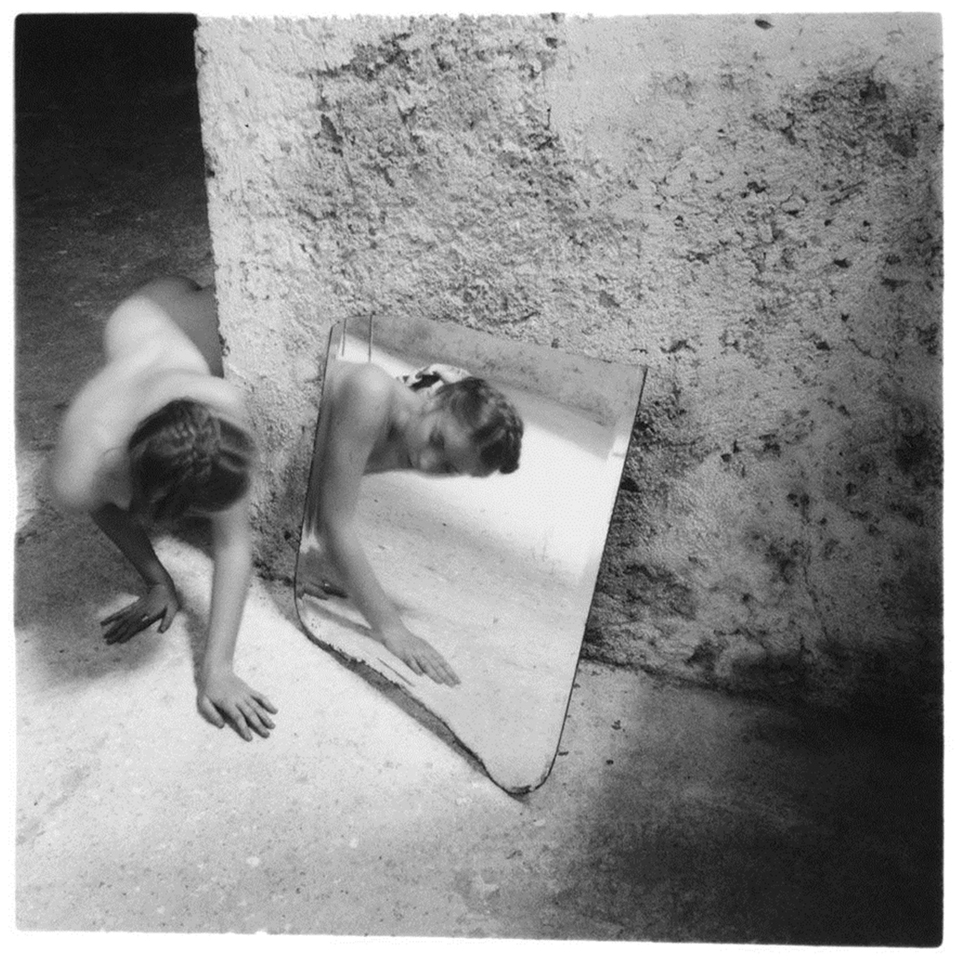

MAD: I wanted to ask about your essay on Francesca Woodman. I like how you connect her work to Surrealism, and also your observation that she short-circuits the conventional binary between subject and viewer. She was a young woman who used herself in haunting images and I supposed her suicide at age 26 amplified the sort of angsty solipsism that some people attribute to her work. I could be wrong, but I felt as if you were implicitly defending her against accusations of narcissism.

DLS: That’s the fallback criticism of any woman who turns the camera on herself, that she is a narcissist. That essay on Francesca Woodman was very difficult to do, because I spent time with her mother and father, and I felt a responsibility to them to be fair to their daughter’s work, and to say something about the work that had not already been said, which was challenging because a lot of very good writers had already written about her. I needed to take cognizance of the work’s place in feminist history and by that time she had also already been taken up as a postmodern avatar, so I had to deal with that, as well. Clearly she had a relation to Surrealist photography, and Rosalind Krauss had already opened up new territory in relation to photography and Surrealism. So my essay was trying to do a lot of things at once. I was pleased with what it finally came to, but it was very hard to get there.

MAD: As with any artist who dies young, especially one who dies at their own hand, it’s hard to see the work for what it is, to penetrate the aura of tragedy and doom that envelops the work posthumously, as if they were forever burdened by the weight of their own vision. I think your essay gives her work a life outside of that dark aura.

DLS: Thank you. That was what I was trying to do. I wanted to explore how we believe images, how they control us and how we receive them. I still think we know very little about how that happens because so much of it lies in the unconscious and in unconscious reactions. That is the nature of images, that is how they work, but getting to that through writing is extremely difficult.

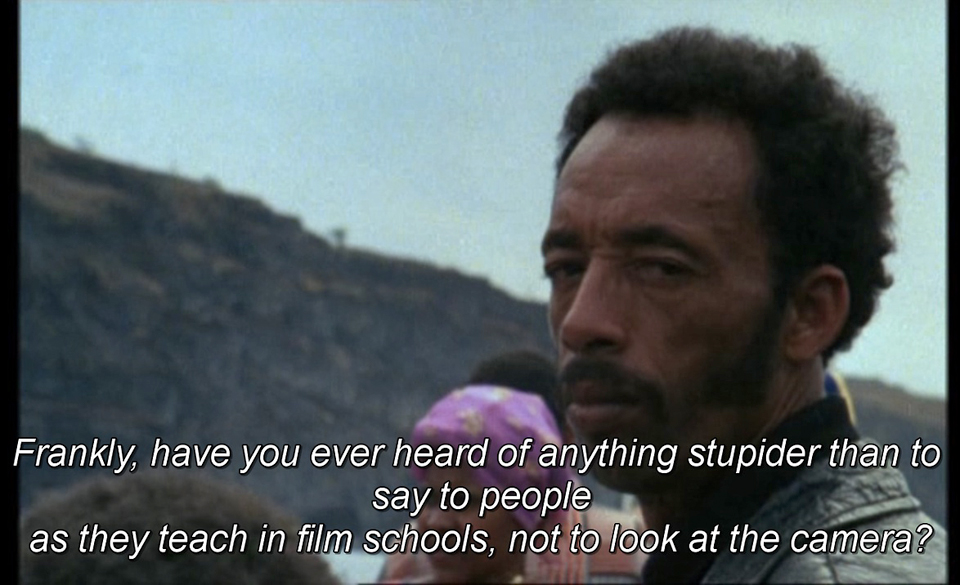

MAD: I think you would agree that Chris Marker explores this territory in film in both fictional and documentary forms. La Jetee is about a man “marked by an image,” and he uses photographs as portals, to travel in time. In his documentary films, Marker is always interrogating himself as he is looking. He examines the image and examines his reactions to the image and in the process he interrogates the language and discourse around documentary practices. In Sans Soleil, he films people looking back at him as he films them and the narrator says something like “Isn’t it stupid what they teach you in film schools, that people shouldn’t stare back at the camera?” Marker acknowledges the exchange, that the subject is being aware of being represented and that is important because it speaks to the power dynamic in representation and, to go back to our theme here, it speaks about the subject and the viewer in relation.

DLS: One of the things that photographic images do is to trace the relation between the person behind the camera and the person in front of it.

MAD: That’s what you explore in the Woodman essay.

DLS: Yes, which is complicated in her images because she is both behind and in front of the camera. She was a prodigy, and there are not that many prodigies in photography. She was involved very early on in a deep inquiry into the self, identity, and the body.

MAD: Let’s talk about the new book. First of all, there is the unusual title, Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow.

DLS: I am happy that title survived, because I really wanted it. Obviously, it is too long and too complicated for a book title, but it is a phrase that has been with me since before being at the Visual Studies Workshop. It is the first line of a poem by the photographer Frederick Sommer, who used it in a 1962 issue of Aperture devoted to his work. And I think the idea has become more and more relevant as a kind of lyrical description of what I have spent much of my life doing—setting up an economy of words and images based on how the two affect one another and what happens between them. It’s outlandish to think that words and images have an economic relationship, but it carries the idea that if you don’t use words to describe images, they lose value and will “buy smaller images” tomorrow; that is, they will have less purchase on images, and it will be harder to do later. I think that is literally true. We now live principally in this screenal world, wherein we are inundated with so many more images moving at a greater velocity than ever before in history. Like Paul Virilio said, the scale, frequency and speed of it has a politics. I am not so sure about the subtitle of the book (Laughter).

MAD: I have a different question about the subtitle (Laughter), “Essays on the Present and Future of Photography.” It suggests a shift in photography in terms of what it was, what it is, and what it might become. As you just said, one of the most fundamental ways in which photography has changed is that we see and receive the vast majority of our images on screens, as opposed to in books or magazines or on walls. Related to that, a photograph’s specificity as an object has become virtual, instantly clickable and just as quickly disappearing. The photograph’s presence has become more fugitive, less fixed in time and place.

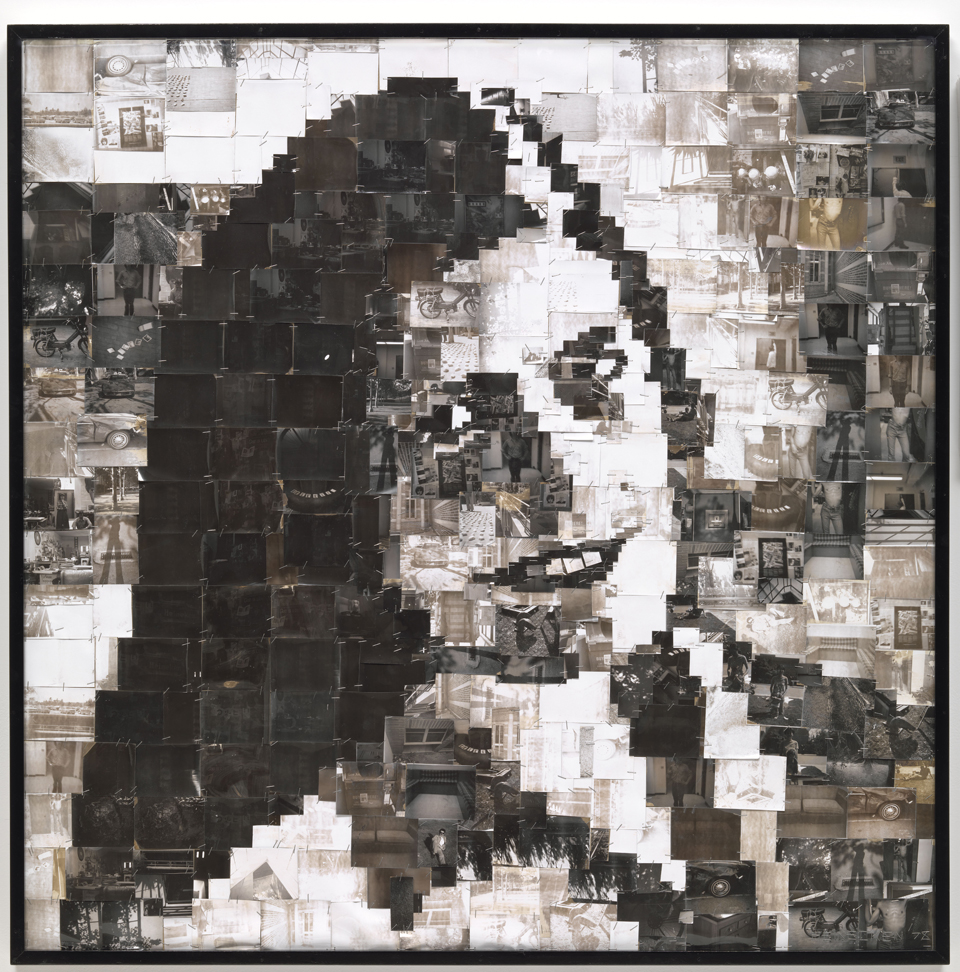

Robert Heinecken, The S.S. Copyright Project “On Photography”, 1978, (collaged portrait of Susan Sontag made from black and white instant prints)

DLS: Yes, but there are always two different things going on. Sontag’s earlier view was that, as the frequency and number of images increased, their affect on us lessened, especially when you are talking about images of conflict or suffering. Our ability to respond decreases as the number increases. She modified that view in her last book, and stepped back from it, and I agreed with her. But the conventional view remains, that we are less subject to images because of the way images are delivered. I don’t think that is necessarily true. There is still a basic human need for iconic images; this was in us long before the invention of technical images, with religious images especially. It’s strange to even call it photography anymore, because it’s not light writing, it’s something else. Those screenal images, skittering online images, are changing us in some ways, but it does not change our fundamental need for images. I think we are mostly operating under a collective hallucination that we know what they are and how they work.

MAD: In that case, what you do is dream interpretation. (Laughter)

DLS: Yes, I like that.

MAD: The dreams keep coming, they never stop, and we may not know what they mean, but we need to respond.

DLS: I always liked James Hillman’s idea about dreams. In response to the dream interpretation fervor a few decades ago, his contention was that we don’t need to interpret dreams, because they are going to do the work that they need to do, which is essential, regardless of our attention or analysis. We know that a person can go without sleep for some time, but cannot live very long at all without dreaming. If you don’t dream, you die. This is close to what is going on in the image environment, which never ceases to fascinate me. If we don’t absorb these images, we fade. There is so much work to be done there.

MAD: 2014 is the 50th anniversary of the publication of Susan Sontag’s essay “Against Interpretation,” which I recently re-read. I don’t have to summarize it for you, but I’ll just say that she argues for an experience of art that does not bow down to some insistent or impatient need to know what it means. She claims that interpretation can be stifling, that we suppress our phenomenological experience of an artwork in the service of categorizing it. This is an ongoing challenge; it’s a 50-year-old challenge. Do you still value that challenge, does it remain a productive one for you?

DLS: Yes, I think Sontag’s challenge is still there, undiminished. In fact, it has increased in importance. I am running this program at the School of Visual Arts in Art Criticism & Writing, really Art Writing as Literature, and the thing that I find is that, even though the students come here wanting to write about art, it is often initially difficult for them to actually look at a work of art without having a theory about it beforehand. Interpretation precedes (and precludes) perception. One of the first things I do is to put up two works of art on the wall, side by side, and have them just write their responses on the spot, without first knowing who the artist is, or what the context or circumstances of the work are. Leo Steinberg always said that an artwork will tell you how to respond to it, if you actually look at it and pay attention. I think it is still risky, even dangerous, potentially, to look at a piece of art and take it seriously, because it will change you. It has changed me. I think you have to slow things down in order to see them. My students hear me say that all the time.

MAD: It’s a bit ironic that 100 years ago, the Futurists and the Soviet Avant Garde celebrated speed, simultaneity, fracturing, in order to esthetically embrace the 20th century. We live in that collaged and fragmented future they so desperately wanted, except we got it without the redemption and liberation promised. I think you are right that now it is a matter of slowing that is the radical act, to slow it down is to oppose it. I don’t mean in some Luddite fashion, I mean slowing it down to really look at what is happening.

DLS: That is difficult to do now, because all the pressure is to keep moving, and to accelerate.

MAD: This is sort of out of the blue, but is there an artist, photographer, artwork or image that you are moved by but have not written about, that you would like to write about but for some reason you cannot find a way to do so?

DLS: That’s an interesting question. One example I can think of, which is an odd one because it’s right in the center of this documentary vs. art photography split, is the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson. I have never written about his work, because to me it is perfect. (Laughter) I need some kind of friction to start writing, to get at the work, and to me his work has always been self-evident and self-sufficient. So there’s kind of nothing to say about it; or I don’t know what to say about it. It’s perfect.

MAD: Does that have to do with virtuosity? Sometimes, in the face of virtuosity one just admires it and moves on because for me it is the flaw or the failure or the limitation that can be interesting about an artist, because it can illuminate so much about the artist’s subjectivity. Failures are interesting. When I teach the History of Photography, obviously I am going to talk about Cartier-Bresson, and I do admire him, but I don’t find him that interesting. In terms of those early mid-century flaneur guys, I prefer Brassai and Kertesz. I am intrigued and still beguiled by many of their images, because I think their concerns were smaller, more eccentric, more obsessive, than the universalizing decisive moments of Cartier-Bresson.

DLS: There are artists that I have written about whose work I keep coming back to—Carolee Schneemann and Alfredo Jaar, for example. Because there is always something unresolved in my own response to the work. The problems are what make me want to write about it. My boundaries get threatened by the work, some boundaries I didn’t even know were there, and that is the way in.

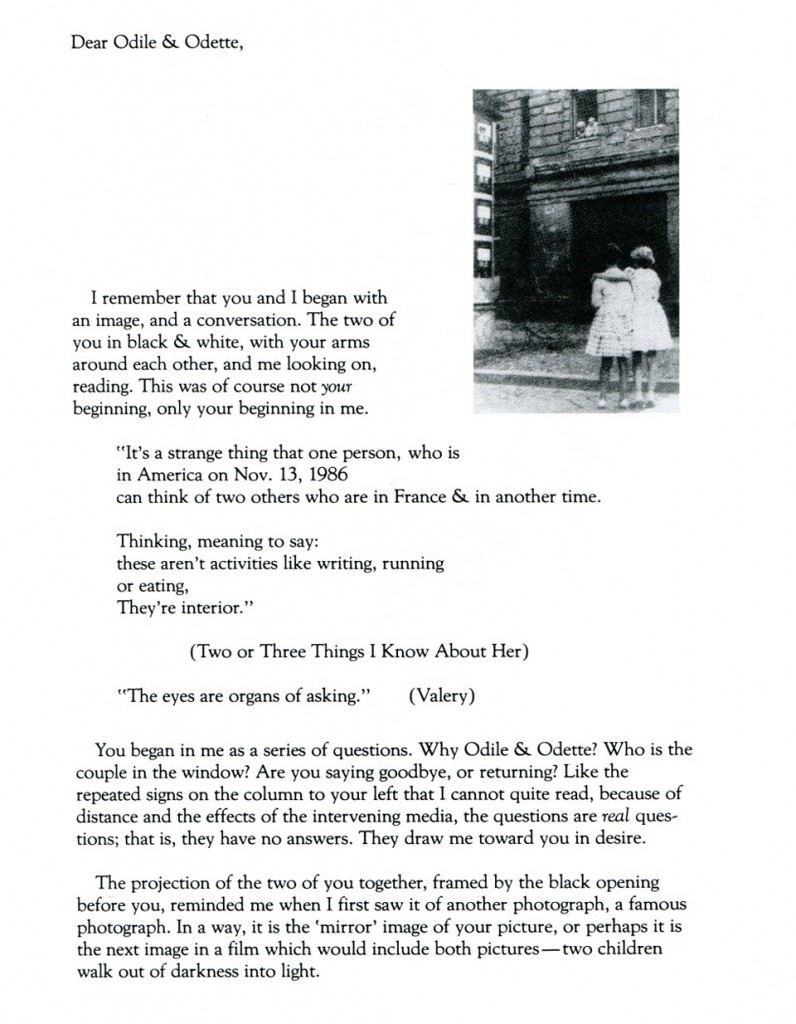

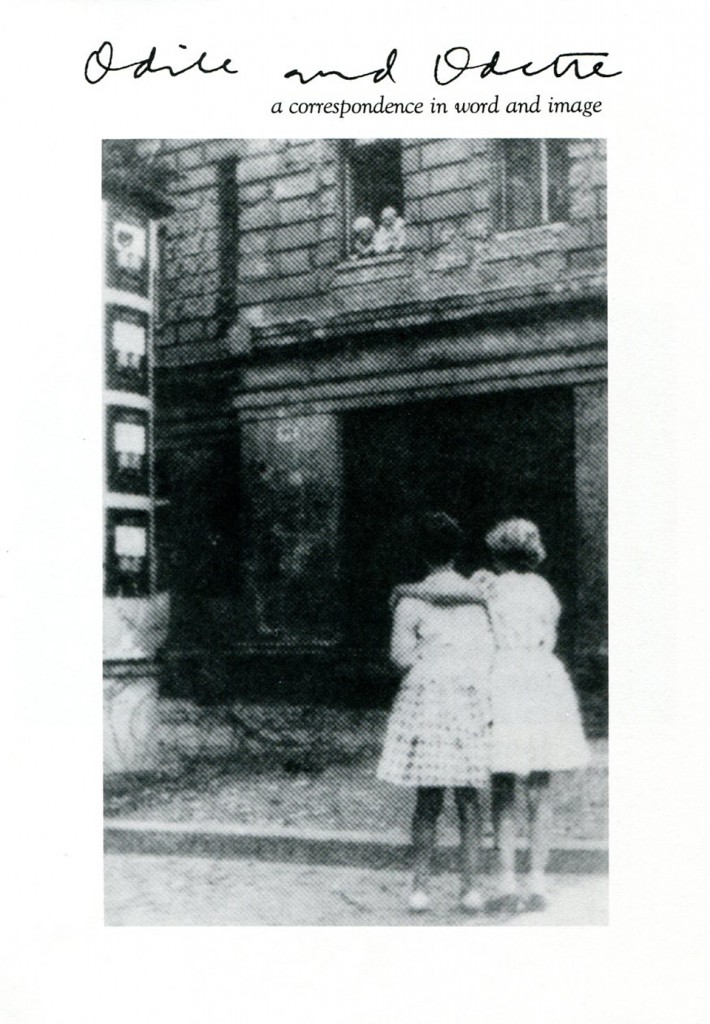

MAD: One last thing I wanted to talk to you about. You have an image/text piece that you worked on years ago called Odile & Odette, which are the names of the principal characters in the ballet Swan Lake. I know you have done a variety of iterations of it. Can you talk about it a bit, what it did or does for you? It begins with an image of two girls standing with their backs turned toward the camera. They are on a street in, is it Berlin?

MAD: One last thing I wanted to talk to you about. You have an image/text piece that you worked on years ago called Odile & Odette, which are the names of the principal characters in the ballet Swan Lake. I know you have done a variety of iterations of it. Can you talk about it a bit, what it did or does for you? It begins with an image of two girls standing with their backs turned toward the camera. They are on a street in, is it Berlin?

DLS: I have never known where the picture was taken. It could be in Berlin as the Wall was going up. It could be in the Warsaw Ghetto. Two young girls stand arm-in-arm, in front of a barbed wire barrier, looking up at a couple in a window above. The poet Norma Cole in San Francisco gave me the image years ago in San Francisco, and I just started writing letters to these two girls in the photograph: Odile & Odette. It became a way to address dualities: word & image, masculine & feminine, love & war. I was travelling a lot at the time I started this writing, so I’d go to Cuba, Russia, or Berlin, always looking for Odile & Odette, and finding them everywhere.

MAD: It is epistolary.

DLS: Yes, it’s all letters to them combined with images, and I found I could address almost anything in these letters to these two imaginary girls. Well, not quite imaginary, since they exist in an image. It has always been about the relation between the past and the future, between politics and aesthetics, between words and images.

MAD: The girls are twinned, together but separate.

DLS: Yes they are two, together. At some point in the letters they become my wife Sterrett and my daughter Maya, or my two older sisters, or other pairs. I have another book of essays I am finishing, and after that I would really like to do a book of Odile & Odette, if I can find someone to publish it.

Again, it’s the relation between the text and the image that is endlessly fascinating to me—what happens between the two. As I say in the introduction to Words Not Spent Today, words and images are antagonistic to each other. In our reading of them we always want the text to explain the image and the image to illustrate the text. To do something other than that is, I think, very generative. I spent some time with John Berger in his home in the French Alps a few years ago and he gave me several assignments, of things that I had to do, and the Odile & Odette book was one of them.