Eileen Cowin

I remember so many things

So many evenings rooms walks rages

So many stops in worthless places

Where in spite of everything the spirit of mystery rose up…

– Louis Aragon, Poem to Shout in the Ruins

the bells chime for no reason and we too

chime bells for no reason and we too

will rejoice in the noise of chains

that will chime within us with the bells

– Tristan Tzara, Approximate Man

In the attempt to brush off the dust of the 19th century and ring in the fresh years of the new century, the Futurists penned manifestos endlessly proclaiming the messianic character of the modern world. They embraced a culture of image and information as opposed to the 19th century culture of the written word and myth. The aesthetic revolution as predicted by the Futurists has come to pass; speed, simultaneity, repetition, fragmentation and incessant war have become the dominant characteristics of our era. Citizens of the early 20th century spend enormous amounts of physical and psychic energy filtering out imagery from their consciousness.

Most images have become enemies in disguise, beautiful poisons we try not to swallow because once ingested they are difficult to dislodge. We have developed skills with which to read images without internalizing them. Knowing this, how can an artist respond to the glut, the avalanche of images that make up our everyday lives and the viewer’s resistance to full engagement? The photography and video works of Eileen Cowin suggest a reversal of our rapid image processing abilities. Paradoxically, she utilizes contemporary technologies (photography, video) and references popular culture (film, television) to create meditative sites that can act as antidote to our ravenous image consumption. Adorned and occupied by Cowin’s images and installations, the gallery and museum become public places for private contemplation where an intimate relationship to the image can be resuscitated.

Cowin’s photographic sequences and video passages present images and words floating in the dark, familiar yet askew, like a film that’s fallen off its reel scattering narrative fragments across the wall, related but irrevocably wrenched from linear storytelling. Even her earliest works, the gum bichromate pieces of the early 1970s for example, reveal an interest in a multiplicity of perspectives, an assembling of personal symbols and cultural motifs, a layering of imagery suggesting stories. In her work of the 1980s and 1990s, Cowin directs a stage of multiple moments, filled with narratives. Much like a literary filmmaker she embodies the directorial mode of artmaking: storyboarding, scripting, staging, working with actors and determining camera perspective. Her “set” is inhabited by clusters of symbols and animated by human gestures that together conspire to create associations in which meaning can be inferred at best. Family snapshots, Renaissance painting, and the visual language of film are primary sources for Cowin’s domain of gestures, and although this repertoire may spark a sense of recognition, we cannot, as viewers, “read” her work with any real certainty. We cannot process her imagery like so many commercials or TV dramas. It is this slippage between image and concrete meaning, between the familiarity and the unknowability of the everyday that reminds us that, like her art, the real meaning of our personal and collective relationships is elusive and full of ambiguity.

One Night Stand (1977-78) is a suite of images that has both conceptual and narrative elements. The tone and color of the photographs are flat and unaffected, a strategy in keeping with the minimalist and non-theatrical aesthetic of the time. Yet even these distancing mechanisms do not obscure Cowin’s playfulness and interest in the structures of intimacy. Polaroid snapshots appear in each of the larger color images; photographs of photographs create frames within frames making a kind of duality of instants. The nightstand is a humble piece of furniture, it sits loyally, and with little fanfare beside the dramatic presence of the bed; it is a supporting character in our daily routines and asks little in return for its services. A night stand may hold a water glass, eye glasses, skin lotion, birth control devices, pictures of family, prescriptions, bedside reading, and may also bear silent witness to a guilty one night stand with an inappropriate but fabulous lover. Within the frame of these large color photographs, miniature nightstands appear sitting atop nightstands of normal scale. Instant photographic prints of men and women in various stages of disrobing peak out from behind phone cords and alarm clocks, betraying what might have occurred in these rooms just moments before. The diminutive representations of bodies and objects imply an assertion of control, an attempt to script the chaotic consequences of intimacies unleashed. This dance between formal rigor and emotional depth is characteristic of Cowin’s entire body of work.

The photograph is a vessel of containment; within the boundaries of the image is a contained and confined world. If meaning is simply an agreeable arrangement of the chaotic, then with the frame the camera offers, and the frame the photographer imposes, comes the promise of meaning. For over 150 years this has given photography its evidentiary power – a photograph as encapsulated meaning – sometimes easy and at other times harder to swallow. This metaphor begins to break down with Cowin’s photographs, for despite their apparent familiarity they resist encapsulation. Historically, photographic meaning falls into either of two categories, the fictive and the documentary. In Family Docudramas, Corwin collapses the oppositions between notions of truth and fiction in photography. Operating in some liminal space between soap opera and conceptual art, Cowin facilitates a spare and collaborative project with actors who are also family members. This ensemble features sons who look like their fathers, sister who could be twins, faces and gestures that mirror one another incestuously. In these works a formal tension is developed when the snapshot is transformed with the heightened sensuality of art.

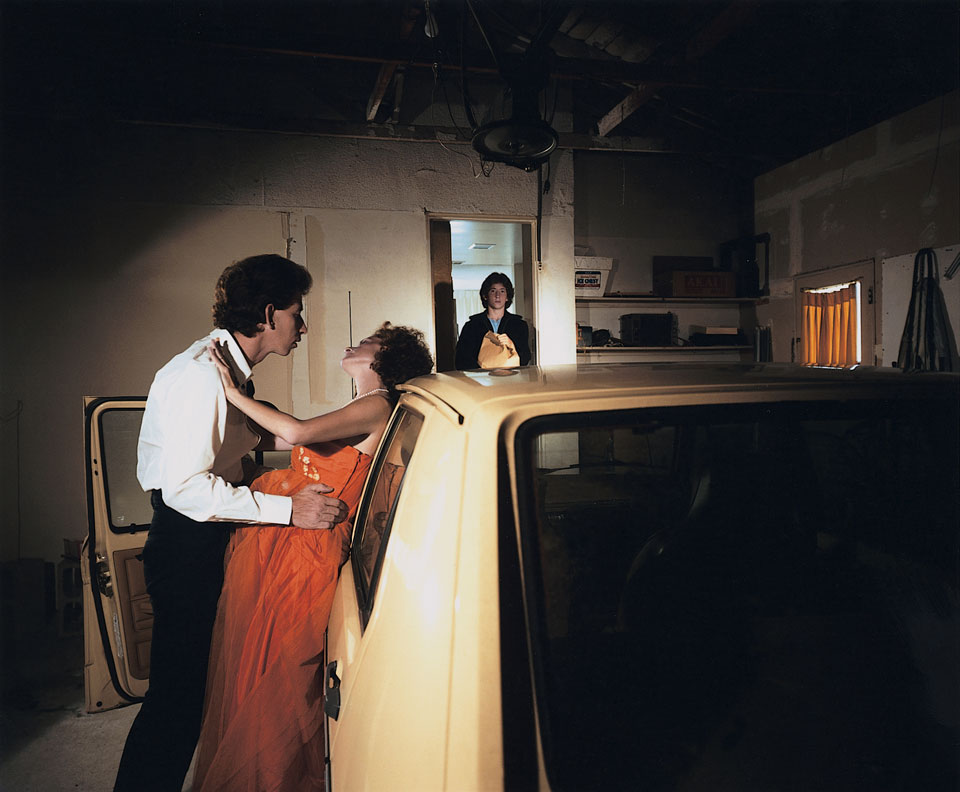

Family Docudramas (1980-1982) is a dance masquerading as a soap opera in which Cowin choreographs the awkward grace of adolescents inevitably out of step with the murky intentions of adults. Like an updated version of Buñuel’s Exterminating Angel, these are disaffected period pieces, performances in which a certain American family is trapped in a farce of manners, caught in a web of social construction. Some argue that all photographs are intrusive. If so, what world is intruded upon in this series? Her actors acknowledge the presence of the camera and, by extension, the gaze of the audience. Her images call attention to their photography qualities on both the cultural and structural levels. In this way, Cowin suggests that he incessant spectacles of photograph, cinema and television have blurred the boundaries that separate the public and the private. Perhaps more insidiously, Family Docudramas suggests that we have become pathologically self-conscious to the extent that even in our most private moments we are aware of ourselves as images and as performers.

While living in Chicago, Cowin often rode the elevated subway in which noisy tracks closely pass by the windows of apartments and office buildings. As the lights come on each evening, a passenger on the train becomes audience to hundreds of split-second scenarios that glow individually in the night like so many lonely candles. In rapid succession the guilty pleasure of voyeurism is turned off and on, off and on, in synch with the staccato rhythm of the shuffling train. A soon as one spies into the kitchens and living rooms of strangers, the train moves on, teasingly offering other tantalizing but ungraspable secrets. This urban/optical phenomenon inspired by Cowin to investigate darkness as an elemental editing technique. By surrounding and inserting inky blackness between images, she could dramatize the appearance of an image as if it were emanating from the night, and also make seamless the continuity of seemingly unrelated imagery.

Cowin combines this strategy born of modern culture with Biblical metaphor in Lot’s Wife (1991). The fate of Lot’s wife unfolded in the shadow of God’s revenge against Sodom and Gomorrah. Reviving this allegorical fable about what is allowed to be looked upon and what is forbidden, Cowin redresses the tale in the costume of film noir. Her characters occupy the symbolic realm like insecure gods, mythic and vulnerable. A veiled bride, reminding us of one of Julia Margaret Cameron’s women, gazes to the right toward the interior of the narrative. This image is followed by a series of isolated dramas: a lacy-curtained window framing a television surveillance monitor on which a hatted man walks away; a woman nervously sits upon a park bench alone and stares back at the camera; two white-shirted men throw undetermined projectiles toward some off-camera target; a German shepherd lopes forward lowering its head menacingly in animal self-containment. If counting from left to right, the eighth image reveals the same veiled woman looking back. According to the book of Genesis, Lot’s wife is turned into a pillar of salt as punishment for disobeying God’s command not to gaze upon Sodom once they had fled the city. Cowin presents her just as she turns; curiosity is a tragic flaw and fierce and an unforgiving Jehovah punishes her. The image on the far right of the sequence shows a pair of men’s shoes standing on a ledge; darkness looms just beyond the toe tips. Does he stand at a precipice of an abyss, or the edge of a stair? Is it curb of cliff, roof or roadside? Is this Lot reflecting upon his loss? Or is it God himself masquerading as a Raymond Chandler character, omnipotent and detached, gazing upon the tragic ends of his creations?

I’ll Give You Something to Cry About (1996) features a dozen images that evoke the passion and dissolution of a union of two. Combining what appear to be stills from old home movies with more contemporary symbolic moments, Cowin distills a lifetime of gestures down to a small cluster of image/memories. A man wraps his arms around a woman, affectionately yet forcefully pulling her face towards his parting lips. A finger retreats from a piercing thorn, a drop of blood stains both the tip of the thorn and the tip of the finger; the wound has bound these objects forever. With the wound lies the potential for compassion for, as Barthes has suggested, the wound is the entrance for love. Other images in this grid further choreograph this dance between man and woman in pendulum swings between lust and anger, connection and isolation. Two badly bruised feet rest upon a bed. A man’s hand displays an open wound. A fist clutches a stack of letters. A man’s mouth widens, agape in anger or laughter; and, in an image suggesting the dreamy after-moments of making love, two windows with delicate veils soften the lovely late afternoon light outside. In the lower right-hand corner, a woman’s face turns away; is she turning away from the kiss in the first frame? By unleashing the chaos beneath the robes of angels and making us capable of betraying God for an earthbound taste of the divine, a single kiss and astonish the heart.

Every relationship of any consequence comes with the promise, “I’ll give you something to cry about.” For Cowin that promise is both a threat and a statement made by a storyteller who can and will provide a tragic narrative for the tear-prone listener. Does narrative save us from getting lost in the inchoate and episodic character of our lives? Does narrative provide an anchor of stability without which we could never survey a horizon line for perspective? Or does our narrative dependency sentence us to a life of illusion, of false security that will ultimately turn our lives into a farce? Cowin does not answer these questions for us, but in her work she navigates the choppy seas, perched high in her crow’s nest above the watery tumult. With piercing eyes she looks for land and searches for survivors who may have lashed together for a few fragments of words and images in the hopes that these temporary and fragile vessels of meaning will keep them from sinking amid the waves.

Cowin offers us an experiential art that is esoteric and accessible, simple and monumental. Cowin blurs the boundary between the still and the moving image. She shows us the strange grace of gestures that float free of an anchoring liturgy; she describes unnamed rituals that occupy dark corners, and suddenly and temporarily she freezes them within the elegant frame of her camera. Cowin’s images capture encounters in the shadows; her characters populate the edges of darkness, a limbo between the chaos of hell and the heaven of eternal illumination. Caught that this threshold we discover the ambiguity that is fundamental to our human experience. Although the eyes of the loved one are enflamed, we fear that the brightness and warmth will bring only a momentary certitude. We stand in that brief glow, a flickering against the larger darkness, wanting more but, considering the alternative, it will have to suffice.

Originally Published in still (and all): Eileen Cowin, Work 1971-1998, curated by Sue Spaid, Armory Center for the Arts, 2000