Civil War in my Heart

SINCE 9/11, the electronic traffic signs on 1-95 between Baltimore and Washington have read “Report Suspicious Activity” followed by a 1-800 number. Whenever I see a Bush/Cheney bumper sticker I am tempted to call. Often the District of Columbia (along with New York City) is on a higher terrorism alert than the rest of the country. Generally this means Orange. When this is the case, checkpoints appear on the roads approaching Capitol Hill, the White House, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Washington Monument. I spent the weekend before the 2004 Presidential Election in Washington, D.C. wandering around the Mall, visiting museums and feeling hopeful for the first time since the last national poll. I thought it was a done deal (being from Boston myself) when the Boston Red Sox won the World Series in four games straight, beating the St. Louis Cardinals on the night of a full lunar eclipse. It appeared to be a unique historical moment when the cosmological would meld with the urgently political. The gods might be on our side for once. From my incorrigibly superstitious perspective, all signs pointed to the inevitable – that John Kerry, the Senator from Massachusetts, would win the hearts and minds of the American people.

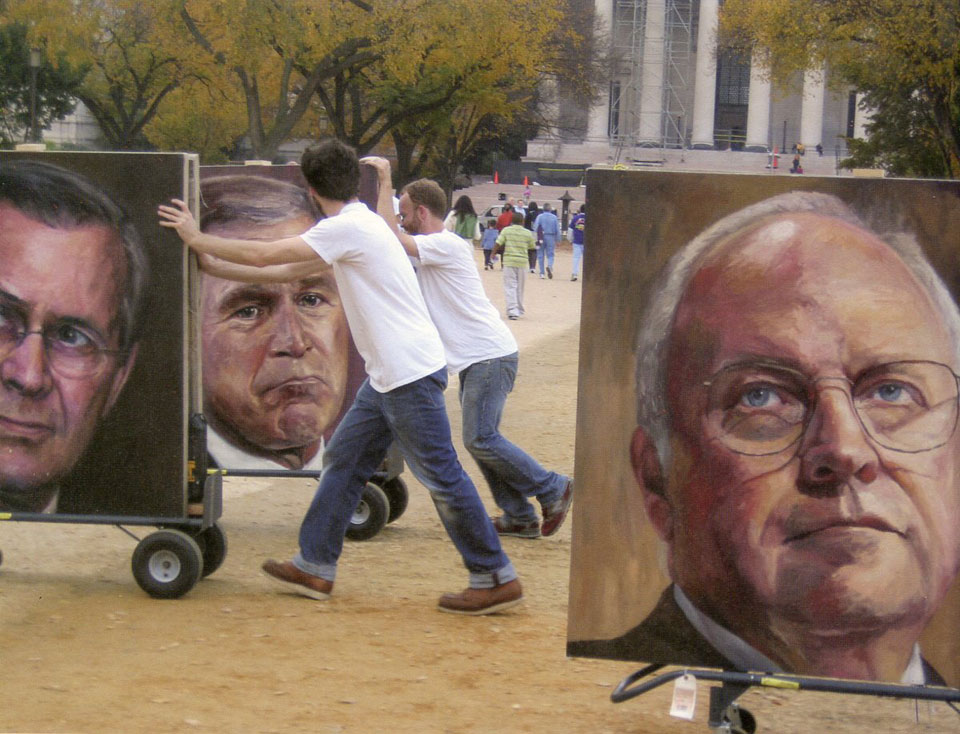

While crossing the nearly empty Mall from the Hirshhorn to the National Gallery, I practically collided with three young men, each quietly pushing a wheeled cart. On the carts were double-sided portraits of political figures associated with the invasion of Iraq: Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Powel, Rice, and Tony Blair. These photo-realistic images did not betray partisanship, they were not caricatures, were competently painted and neutral in tone. Yet there was something undeniably ominous in this unspoken ritual. Were these figures being symbolically escorted from power like deflated icons? In which case I loved the idea of this sparsely attended funeral. Or were we being reminded of the ideologues that lurk and conspire behind the walls surrounding the Mall and that would not surrender so easily? Whatever the intent, I was mesmerized by their slow passage toward the Washington Monument. In this historically significant site – where so many marches and demonstrations have occurred over the last 100 years that its inclusion or citation seems now almost a rote gesture of political opposition – it was amazing to me that such a simple action, both anachronistic and contemporary, could generate such contemplative power.

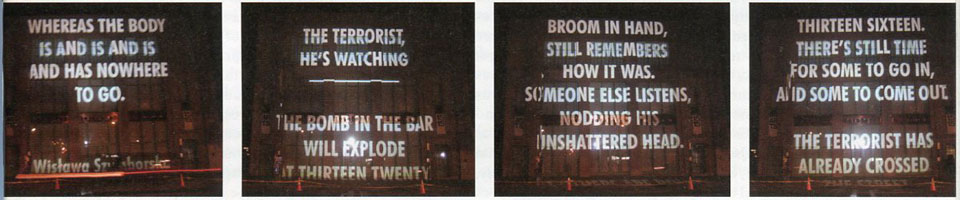

That same evening, a few blocks away Jenny Holzer was commissioned to project a work onto the façade of a new arts complex on 14th Street. Instead of the usual truisms and aphorisms of her public texts, Holzer chose to project the poems of Wislawa Szymborska, the Polish Nobel Laureate. Several dozen onlookers kept vigil at any given time, and while there was some hushed conversation the somber tone of the poems focused our respectful attention. The poems were projected throughout the night from dusk to dawn, slowly scrolling up from the street level toward the top of the three-storey building, from where they seemed then to slip off into the ether: On this third planet of the sun, among the signs of bestiality a clear conscience is Number One.

Like other great Polish writers, including Czeslaw Milosz, Tadeusz Konwicki, Witold Gombrowicz and Zbigniew Herbert, to name a few, Szymborska understands the treachery of history. This is not surprising considering the Polish experience of the twentieth century. And while easy historical comparisons are cheap, it is absolutely uncanny how the sensibilities of poems like “The Terrorist, He Watches,” and “In Praise of Feeling Bad About Yourself” seem to embody our current political climate. As police cars sped by and SUVs slowed down to read the projection, I got into a sudden and violent debate with a Ralph Nader supporter. We traded hateful and sarcastic words beneath Szymborska’s tragic texts of dread and pathos.

THE DISTRICT of Columbia was created in 1791. Pierre L’Enfant, one of the principal designers, wrote to George Washington in 1789, “that the plan should be drawn on such a scale as to leave room for that aggrandizement & embellishment which the increase of wealth of the Nation will permit it to pursue at any period however remote.” L’Enfant’s plan, although appropriately grand in scale as to compete with Paris, was never fully realized. Pennsylvania A venue, connecting the White House and Capitol Hill, was built wide enough to accommodate marches and parades, yet several blocks nearest the Capitol Building soon gave over to saloons and prostitution. The Mall remained largely undeveloped with shantytowns spreading along its swampy edges until the mid-nineteenth century when its expanse was landscaped as a kind of Victorian park with curving pathways for carriages. L’Enfant’s vision of the Mall as a site for large-scale ceremonial events was finally made manifest in the early twentieth century when a Park Commission-that included Daniel Burnham and Frederick Law Olmsted recommended the design that we now recognize as that long and narrow strip of grass between the Capitol Building and the Lincoln Memorial.

Memorials and museums; statuary and neoclassical architecture; patchy grass; the shallow, goose-filled water of the Reflecting Pool; and a massive white obelisk: these are the material features of the National Mall, the ceremonial axis at the political center of the United States. The gleaming white buildings of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches adjacent to the Mall symbolize our representative democracy, and these universally familiar anchor points are linked by a sequence of grayer structures housing more inscrutable institutions. Although there were nine previous sites of the American capital in the first years of the Republic, the fact that its permanent home was built here in the swampy land off the Potomac River was no mistake. Its distance from the competing economic and cultural powers of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia was a political compromise (George Washington owning land in the area didn’t hurt, either). But perhaps most importantly, its isolation promised to keep the governing representatives far removed from the uncomfortable demands of its citizens.

The Mall has been the site of countless gatherings of those demanding citizens, some momentous, some barely noticed, but all have provided examples of direct democracy in which the government and its policies are challenged by the emphatically present bodies of protestors. Despite the fact that in 1882 Congress prohibited the carrying of banners and the making of “any oration or harangue” on the Capitol grounds, the first amendment of the U.S. Constitution guarantees the “right of its citizens to assemble and petition the government for the redress of grievances.” And since the late-nineteenth century, the Washington Monument has functioned as a kind of activist Maypole, around which millions of Americans have assembled. The first significant march on Washington was by “Coxey’s Army” in 1894. Jacob Coxey organized hundreds of unemployed men to march from his hometown in Massillon, Ohio to Washington to petition the government to provide monies for a national road building program. This “Petition in Boots,” as it was popularly called, was demeaned in the press as a sign of fatal “blood poisoning in the republic.” After Coxey’s arrest and imprisonment, his demoralized followers spent much of the summer camping around the mosquito-infested Mall. Although “Coxey’s Army” was not successful in its demands, it did set a historic precedent, claiming the ceremonial spaces around the Capitol as “Property of the People.”

As A PRIVATE citizen and as an artist I have my own history here in D.C. For nearly ten years in the 1990s I was part of the collaborative duo Men of the World that performed what we called image/gestures on the streets of most major North American cities. Dressed in white-collar drag, we performed unannounced actions in downtown business districts and pedestrian-filled thoroughfares. One of our on going projects was titled “The Price of Monuments” in which we interacted with various heroic statuary by tying a stringed tag with the text, “How do you think a man like me got to be a man like me?” printed on one side and “This is an Index of Participation in the Collective Sleep” on the other. In 1993 we climbed upon plinths to reach the neo-fascist figures representing the Boy Scouts of America; the diminutive Alexander Hamilton on the steps of the Treasury Department was festooned with our tags, and in the park across from the White House we donned the wrists and ankles of our Founding Fathers. We tagged every object and figure in the Civil War Memorial at the foot of the Capitol Building, and the horses, flags, carts, guns, and soldiers were all transformed into ideological products by the addition of these tag/texts. Except for a few hostile glances from an aimless Vietnam veteran, no one, not one single tourist, nor security guard stopped us or inquired about our activities. The tags remained for the better part of a week. These actions are unimaginable in post-9/11 D.C.

On November 17, 2001, I sat on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in the early evening light, holding hands with the woman I would marry. It was our first date. As if falling from the cobalt skies, a series of jets suddenly appeared overhead lowering their wheels in their approach to the newly reopened runways of Reagan International Airport. Reagan International (one of Reagan’s first actions as president was to fire hundreds of striking am traffic controllers) is a stones throw from the Capitol and had been closed since 9/11 “Jets are Weapons! Jets are Weapons!” was my internal mantra, almost expecting each passing flight to slam into the Washington Monument, whose tip was catching the final soft orange of the day. The public anxiety of the previous two months seemed to wick from my pores as we gazed upon the multitude of American flags undulating across the Mall and the District beyond. I feared all that flag-waving and knee-jerk patriotism of the last two months, while understandable, would function as a blank check for the men in the White House to fulfill a long planned agenda. A year and two months later on a frozen January afternoon, I stood among the bodies of thousands who were protesting the impending war on Iraq. Although many among us cried out, “Not in our Name!” the retaliations began nevertheless.

THE NATIONAL MALL is divided in half by the Washington Monument. The Western side features the Lincoln Memorial, Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the Korean War Veterans Memorial, and the new National World War II Memorial. The eastern end is surrounded by the National Gallery of Art and Smithsonian Museums including the Air and Space Museum, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and the newly opened National Museum of the American Indian. It is an interesting division of cultural memory – war to the West, art and science to the East. The location of the World War II Memorial at one end of the Reflecting Pool provoked controversy because it interrupts the flow of the Mall with a large oval layout permanently occupying the ground traversed by the massive civil rights and antiwar demonstrations of the 1960s and ’70s. Given its dominating neoclassicism, the Memorial is also a kind of aesthetic throwback, as if the social challenges and shifts of the latter part of the twentieth century never happened. The World War II Memorial reflects a cultural wishful thinking, as if we could have a history without the collective shame, embarrassment, guilt, rage, and/or sense of betrayal associated with the Vietnam War.

On Veterans Day 2004, I lurked around the war memorials to observe the observances. If the World War II Memorial’s aesthetics manifests nostalgia for a “good war” fought by the “greatest generation,” the actual behavior of visitors is clearly influenced by the rituals of interaction associated with the Vietnam Memorial, its touching solemnity, tracing the words inscribed in stone, and fragile, makeshift offerings of photographs, handwritten notes and personal mementos. Small bands of high-school ROTC members marched from memorial to memorial, carrying flags and holding salute at the hard-earned notes of the bugle. For many of these kids, joining the military is their only hope of employment, to stay out of jail and receive a college education. In a peacetime economy this is not a bad deal for youth with few options. But now, with the Iraq War draining the resources of our country and the blood of working-class soldiers, this de facto draft throws a harsh light on the inequality of the “All Volunteer Army”. It was an unnerving experience while watching the slightly-out-of-step marching, the ill-fitting hats and uniforms draping awkwardly over the adolescent slouch, the lingering essence of childhood in their faces, to know that in all likelihood the majority of these kids will be fighting in Iraq within a year or two.

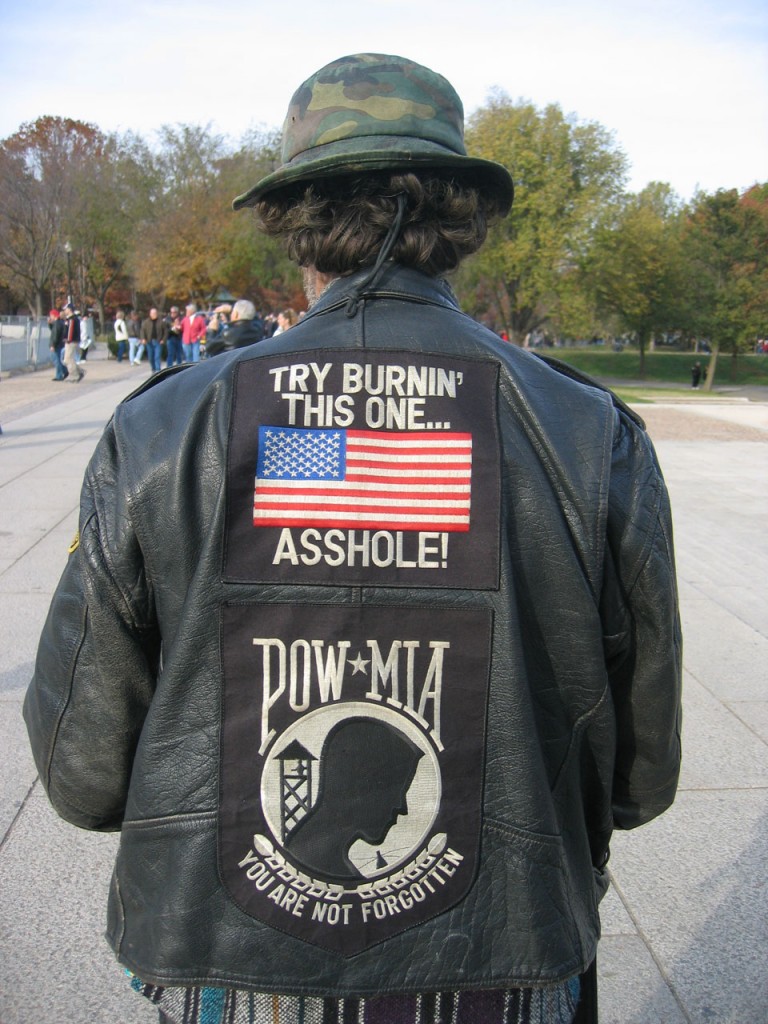

Veterans Day brought out hordes of a very specific subculture: Harley-riding, baseball-hat-wearing, pony-tailed, preferably limping, middle-aged rebels with POW and American flag patches sewn onto the backs of their leather or denim jackets. My brother is one of these men and although many of these biker-warriors are not veterans themselves, the image of the tough, battle-scarred, macho yet unconventional figure is the ultimate romantic antihero of blue-collar baby boomers. The members of this tribe gather especially around the Vietnam Memorial and their presence symbolizes the complicated knot of unresolved contradictions around issues of patriotism, class, and fading echoes of the counterculture. Just what does that forlorn silhouetted figure representing POWs mean? Who is being referred to by the phrase, “You are not forgotten?” Around this icon orbit a number of inchoate political emotions and vague ideologies. On the literal level, it is obvious that it refers to those soldiers missing in action or otherwise unaccounted for in Southeast Asia, allegedly and conspiratorially left behind by an uncaring government. But the fervor and tenacity of those who rally around this symbol illuminates something far deeper and darker. I believe it is class rage tinged with paranoia. In a country that has created an elaborate mythology of individualism with a parallel demonizing of any notion of collective identity beyond “American,” it is nearly impossible to articulate an oppositional ideology without the faint whiff of being unpatriotic. One result of this repression is this hybrid figure of the abandoned warrior/rebel.

Like a skeptical anthropologist, I approached a member of this tribe to photograph the regalia of his biker jacket. He looked at me suspiciously and, as if it were a test, told me an Osama bin Laden joke. He was straight out of central casting with his shaggy hair, bad teeth, alcohol breath and thinly veiled racist comments about Baltimore. I was about to flee from this yahoo when he reached down to pick up an armful of roses and asked if I had been to “Nam.” I said no, he smiled politely, nodded and turned toward the deep cut in the ground of the Vietnam Memorial and as he moved down the pathway, he gave a flower to every Vet he encountered. I walked on, slowly descending into the earth as the wall with its litany of names rose above the clusters of veterans greeting each other with hearty backslaps and complicated handshakes. It is an essential gesture to touch the names, to run your fingers along the grooves. My fingers ran across the letters spelling out “Gerald J. Waalen.” The wall faces south and although the sun had just dropped behind a bank of clouds low to the horizon, the dark glossy surface emanated residual warmth.

At the Korean War Memorial, I thought about my father who fought in that undeclared “police action” after he dropped out of high school to join the Marines. He had never traveled outside a fifty-mile radius of his hometown before he found himself carrying a rifle in the bitter Korean winter. The Memorial itself is a strange affair. It seems to strive for the gravitas of the Vietnam Memorial with its polished stone wall, but instead of names, the faces of soldiers are sandblasted onto the wall’s surface where they float and overlap our own reflections like spirits in a Victorian parlor. What set the Korean Memorial apart are the somewhat grotesque sculptural figures that represent American soldiers on patrol. The figures are a bit larger than life-size, and with hollowed-out eyes and ponchos hanging over knapsacks they resemble misshapen zombie-like aliens who have just been dropped on a hostile planet. It occurred to me that, perhaps inadvertently, the strange contorted figures of the American soldiers might be a vision from the perspective of the native inhabitants of that land afflicted by the Cold War.

Although my father never talked about his experiences, my brothers and I fetishized the souvenir bayonets he brought home and fancied that the spots of rust on the blades were remnants of the blood of the enemy. He also came home with a handful of snapshots – ephemera from that historical collision. The pictures show several of his soldier buddies theatrically playing at hand-to-hand combat while smoke rises on the horizon; a Catholic mass is celebrated from the back of a truck; a harnessed water buffalo stands alone in a field; and a peasant carrying an enormous bundle of kindling on his shoulders stares back at my father. I have always wondered about that encounter between my father and that Korean peasant. How long did they hold each other’s gaze? What could these strangers have understood of each other, both impelled forward by forces greater than themselves? Could there ever be a memorial to a moment such as that?

Occupying the last bit of real estate on the Mall, the National Museum of the American Indian is likely to be the final major architectural project to be realized there. It is surprising that this institution was ever built at all considering its location and the relative lack of political clout Native Americans have on federal policy. Yet there it stands with its curvilinear sandstone facade and huge open atrium within, as if the Guggenheim collided with Anasazi cliff dwellings. Housing over 800,000 objects, the NMAT was designed in consultation with indigenous peoples throughout the Americas. Wanting to serve more as a grand cultural center rather than an ethnographic display of dead artifacts, the museum presents itself in unusual ways, where oral histories and creation myths are presented with state-of-the-art multimedia displays and native ceremonial objects are shown alongside guns and Bibles.

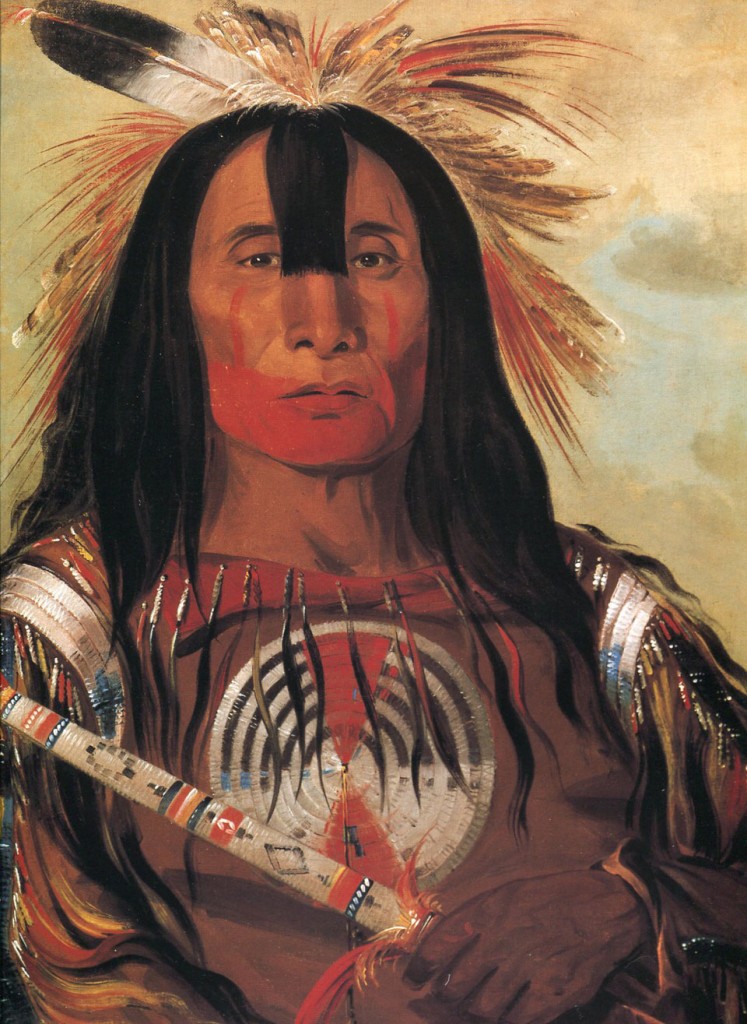

There is a distinct absence of linear time among the displays, because I suppose it would suggest an inevitable defeat of native cultures within the context of Euro-American chronology. The result is an odd de contextualization, providing histories that are at once episodic and universalizing. A revelation for me was the collection of early-nineteenth-century painted portraits of Native Americans by George Catlin. In the decades immediately preceding the invention of photography, Catlin, with a mix of altruism and opportunism, traveled thousands of miles to meet and negotiate with hundreds of tribal leaders to sit for him. The result is an extraordinary archive of likenesses that do not suffer from the domesticated nostalgia of the more well known photographic portraits of Native Americans made by Edward Curtis a century or so later.

With very little fanfare (especially compared to the endless barrage of PR associated with the reopening of the new MoMA this fall), the vast array of museums on the Mall consistently presents must-see exhibitions. For example, during election season 2004, one could see Ana Mendieta’s retrospective at the Hirshhorn, the Dan Flavin retrospective at the National Gallery, an extensive Garry Winogrand show at the Smithsonian, as well as visit the new National Museum of the American Indian, all within a five-minute walk of one another (the Corcoran Gallery of Art-another gem-is closer to the White House). The Hirshhorn is a small miracle of an institution. It is difficult to imagine today when politicians routinely demonize modern and contemporary art if they pay it any attention at all, but in the late 1960s President Lyndon Johnson along with the head of the Smithsonian, S. Dillon Ripley, convinced Joseph Hirshhorn, a Latvian immigrant who amassed this vast body of work, to donate his collection to the Smithsonian by promising to build a museum of modern art on the Mall to house it.

With its 1960s-specific architecture (I love its UFO roundness), one can travel seamlessly through the collection. This is especially effective with the recent retrospective exhibits of Douglas Gordon and Ana Mendieta. Celebrating its thirtieth anniversary this year, the Hirshhorn mounted a series of tightly focused exhibits titled “Gyroscope: Rotations from the Collection” that not only highlighted the depth and breadth of its holdings, but also allowed for a refreshing curatorial playfulness. For example, a room full of body images included a Lucien Freud canvas of pale quivering flesh, a small Degas bronze of a pregnant woman, Balthus’ painting Golden Days (1944-46), John Currin’s The Pink Tree (1999), a Rodin wall sculpture (Iris, Messenger of the Gods, 1890-91), and a large-scale photograph from Sam Taylor-Wood that has an image of a large-breasted sleeping woman hovering over a horizontal panorama of an unfurnished apartment with four midgets staring back at the camera.

A few days after the election, in the lobby of the Hirshhorn, I was watching a documentary about the gunpowder spectacles of the Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang. I exchanged a friendly smile with a middle-aged man in a trench coat. Although deeply embittered by the election results, I was trying hard to feel magnanimous and hopeful being here in this public (and free) museum, this public space for private contemplation in the political heart of the nation. My smile apparently functioned as a green light for a cliché-laden tirade about contemporary art-“This is what they call art today?” ad nauseam. My benevolence surged instantly to rage. I felt as if Karl Rove himself, that evil little tyrant whispering in the ear of our frat-boy president, confronted me. It took all of my self-control just to walk away and not acknowledge his ignorance but for hours I was obsessed by visceral fantasies of ripping his art-hating heart out of his chest and lodging it in his throat, silencing him forever.

Perhaps I am slow, but it occurred to me at that moment that for years, like so many others on the left end of the political/cultural spectrum, I had been attempting not to offend “Middle America.” I had sought a philosophy and rhetoric of inclusiveness that didn’t buy into binary exclusions of right and left, religious and non-religious, urban and rural. This has been a total failure. I no longer feel the need to apologize for art, to mollify Christians by trying to convince them that I too have moral values. I embrace my tribe of artists; my faith in the value and necessity of our individual and collective goals is deep and unshakable. I oppose the moral values crowd with the conceptual rigor of Dan Flavin, with the voracious cynicism of Garry Winogrand, with the somber grandeur of Jenny Holzer, with the fiery explosiveness of Cai Gou-Qiang, and I bless those young men pushing their carts with the faces of those terrible people.

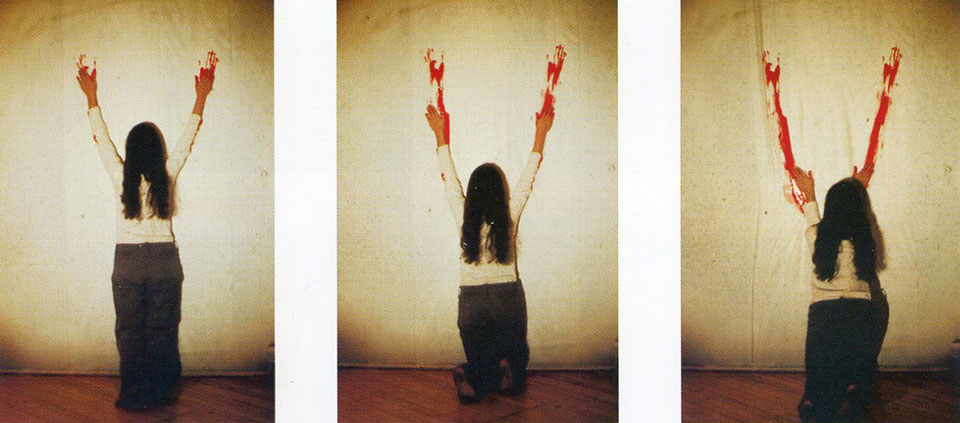

The Ana Mendieta performance in which she draws two lines with her blood-soaked arms has taken on a new meaning in this context. Those lines may curve toward one another and flirt with intersecting, but finally they pull away and stand in strident opposition to one another. These are the bloodstains of the civil war in my heart. The Christian right believes that there is a left/liberal, godless, homosexual, eco-feminist, elitist cabal attempting to seize control of the culture. Well, let’s do it and let’s do it quick. They can rant all they want from their legislative seats and church pulpits but let us poison the minds of their children with the convulsive beauties and contradictory pleasures of our art. Before long, red-state offspring will flee the boredom, homogeneity and intolerance of fundamentalist families, and find home in the polymorphously loving arms of the blue-state tribes where they will walk our chaotic streets joyously proclaiming that they aren’t in Kansas anymore.

Originally Published in artUS, Issue 7, March – April, 2005